Glencairn Museum News | Number 5, 2025

These artifacts, exhibited in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery, provide a glimpse into daily life in ancient Egypt.

Due to the nature of preservation and the Egyptians’ funerary practices, much of what we know about daily life in ancient Egypt is a result of examining materials that were placed in tombs as funerary goods. As early as the Predynastic period (c. 5000–3000 BCE), the ancient Egyptians buried their dead with goods intended for use in the afterlife. These early burial goods included vessels with food provisions for the afterlife, jewelry, and slate palettes (for preparing cosmetics). The burials reflect a belief in an existence beyond death and the idea that the deceased would require material possessions in the afterlife, a belief that continued throughout the Pharaonic period. While funerary objects such as coffins, masks, canopic jars, and shabtis were created specifically for burial, many other artifacts found in tombs were items the deceased had used during their lifetime and wished to take with them to the next life.

Perhaps the finest example of this can be seen in a New Kingdom tomb belonging to a married couple named Kha and Merit who lived in the workers’ village of Deir el-Medina on the west bank of Thebes. Kha was an official who supervised the workers and artisans who cut and decorated the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. He lived during the reigns of three rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty: Amenhotep II, Tuthmosis IV, and Amenhotep III (c. 1400 BCE). Kha and his wife were buried in a tomb known today as Theban Tomb 8 (TT8). This tomb was discovered in 1906 and was found to be intact and completely undisturbed by tomb robbers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A view of the burial chamber of the tomb of Kha and Merit at the time of excavation in 1906 taken by Francesco Ballerini (image courtesy of Archivio fotografico Museo Egizio, Turin).

Excavators found that the tomb was packed with over 400 items including furniture, storage chests filled with personal belongings (Figure 2), clothing, tools, and food such as bread, meats, and fruit (Figures 3a–c). Their well-preserved mummies had been placed in a series of large wooden coffins (Figure 4). Almost all this material is now housed in the Museo Egizio in Turin, one of the finest Egyptian collections in the world. Most of the material in the tomb were objects of daily life that had been placed there for Kha and Merit’s use in the afterlife. This discovery gives us excellent information about the types of things used daily by elite non-royal individuals who lived 3,500 years ago.

Figure 2: Some of the clothing and storage boxes found in the tomb of Kha and Merit (image courtesy of Museo Egizio, Turin).

Figures 3a–c: Kha and Merit’s tomb contained a variety of food offerings including baskets of fruit, loaves of bread, and bowls containing dried meats (image courtesy of Museo Egizio, Turin).

Figure 4: The inner coffin of Kha (Suppl. 8429) on display in the Museo Egizio, Turin. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

Insight into life along the Nile can be gained through the artifacts the ancient Egyptians left behind. In a landscape that combined desert and riverine surroundings, the inhabitants of the Nile Valley established towns and cities where they farmed, fished, and hunted. They worked in markets, administrative centers, and temples. Every aspect of daily life was guided by the principle of maat, the ancient concept of order and balance that sustained the Egyptian cosmos.

We can now turn to objects in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian collection that shed light on the daily lives of ancient Egyptians. Many of these artifacts likely come from funerary contexts, having been placed in tombs to accompany their owners into the afterlife (Figure 5). The Egyptian gallery features a wall case devoted to materials related to daily life, but other objects throughout the collection also contribute to our understanding of everyday activities in ancient Egypt.

Figure 5: The Daily Life exhibit in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery features materials related to everyday activities.

Figure 6: Men are usually shown wearing a short kilt, as can be seen on this standing Old Kingdom ka statue (E1162) and the seated figure of Ineb (Figure 21a), while women are depicted wearing long close-fitting dresses like that seen on Ineb’s wife, Henti (E1151). In contrast, note the voluminous garments from the tomb of Kha and Meryt (Figure 2).

One aspect of daily life that can be appreciated in the Glencairn collection is clothing. The collection houses fragmentary examples of Egyptian fabric made of linen and wool that were originally part of garments worn by the ancient Egyptians. Fashions changed over the long span of Pharaonic history, but some things remained constant. Most ancient Egyptian clothing was made of linen spun from flax. Linen was produced in varying qualities with the finest, sheerest linen being reserved for the king. Representations of men and women can be seen in the gallery. While these images are idealizing, they give us a sense of the types of clothing the Egyptians wore. Men are usually shown in kilts that were often knee-length (Figure 6), but garments reaching to the ankles are also known, appearing on the sarcophagus fragment of Wennefer (Figure 7). A mix of long and short kilts can be seen on the men who appear on the stela of Maienhekau. Women’s dresses in ancient Egypt were typically ankle-length. In statues, wall paintings, and reliefs, these garments often are tightly fitted to the body. However, the actual linen shifts or robes were looser and more tunic-like in form. Clothing made from wool was also known in ancient Egypt. Examples of footwear are displayed in the gallery as well, including sandals woven from reed (Figure 8). Some shoes were crafted from leather and could be elaborately decorated.

Figure 7: Wennefer (E1153) wears a long kilt and has the bald head usually associated with Egyptian priests.

Figure 8: Examples of sandals (E97-102) made of plant fiber are on exhibit in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery.

Figure 9: This lifesize (?) head of a priest depicts him with a shaved head (E1156).

Hairstyles evolved over time, and a number of these variations can be observed in the Glencairn collection. Men are shown with closely cropped hair, wigs of different lengths, or completely shaved heads. Those depicted with bald heads often held priestly roles, as shaving was part of maintaining ritual purity (Figure 9). Women’s hairstyles also display a wide range of styles. They are portrayed with short hair, wigs of varying lengths and volume, or hair (natural or artificial) styled into different forms of braided styles (Figures 10a–b). Children are often depicted wearing a distinctive side-lock hairstyle, in which most of the head is shaved, leaving just a single lock or ponytail of hair on one side. This hairstyle is also seen on certain deities who were represented in child form (Figure 11). Examples of ancient Egyptian wigs have been found preserved in tombs, including the one owned by Merit, the wife of Kha (Figure 12). Tools for personal care and grooming including combs, tweezers, razors, and other cosmetic implements are well represented in the archaeological corpus.

Figures 10a–b: Ruiu’s long full wig is further ornamented by a series of braids that cascade down the back of her head. See the article on this libation basin (E1178) in Glencairn Museum News.

Figure 11: The god Harpocrates (Horus-the-Child) wears the sidelock associated with children (E1165).

Figure 12: The wig owned by Lady Merit (Suppl. 8499) was found in her tomb (image courtesy of Museo Egizio, Turin).

Figure 13: Eye makeup was stored in small jars like this example (E26) made of calcite (Egyptian alabaster).

Both men and women wore jewelry, including broad collars, beaded necklaces, bracelets, armlets, and rings. In the New Kingdom, earrings became popular for men and women. For a discussion of jewelry in the Glencairn collection, see here. Certain magical amulets were reserved for funerary purposes, but many were also worn during life to offer protection or signify devotion to a particular god or goddess. Both men and women wore kohl around their eyes (Figure 13). This mineral pigment, ground on palettes, not only beautified the eyes, but it may also have had health benefits and protected the eyes from infection. Other cosmetics like oils and perfumes would have been stored in small vessels of stone or glass. Highly polished bronze mirrors were used to check one’s appearance (Figure 14).

Figure 14: This bronze mirror (E19) has a handle in the form of a young woman.

Another aspect of daily life that can be found not only in tombs, but also in excavations of houses, villages, and towns is the use of different serving and storage containers made of pottery. Ancient Egyptian ceramics come in a wide variety of forms including cups, bowls, beakers, bread molds, platters, jars, and amphorae. These vessels would have been used daily for the production, storage, and consumption of various foodstuffs including grains, oils, wine, and other comestibles. One can get a sense of the variety of foods enjoyed by the ancient Egyptians by examining not just actual food remains left as offerings in tombs, but also from depictions of food in offering scenes, menu lists (Figures 15a–b), and funerary prayers that describe the types of food being offered. The ancient Egyptian diet was varied. Protein sources included animals such as cows and goats that were raised for food, and fish and fowl caught in the wild (Figure 16). Farmers grew a variety of fruits, vegetables, and grains. Bees were raised for honey. Bread and beer were essential staples of the Egyptian diet, and their production appears to have been closely interconnected. Barley and emmer wheat were primary ingredients in both Egyptian bread and beer. The addition of sweet ingredients such as dates and spices would have enhanced the flavor of the ancient beer. One of the standard funerary offering prayers requests “a thousand of bread and a thousand of beer” for the deceased (Figure 17). The ancient Egyptians also produced wine, which was stored in large amphorae labeled in hieroglyphs with the type of wine and the area in which it was produced, not unlike a modern wine label (Figure 18).

Figure 15a: The mastaba of Tepemankh contains a menu list of items written in hieroglyphs, including foodstuff. This fragment is in the Louvre (E25408) and joins the false door in Glencairn Museum (Figure 15b).

Figure 15b: The false door of Tepemankh in the Glencairn Museum collection begins a menu list of items written in hieroglyphs that is continued on a fragment in the Louvre (E25408; Figure 15a).

Figure 16: Bebi’s son is shown offering a haunch of meat to his father on this funerary stela from Dendera (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, 29-66-668).

Figure 17: Offerings of bread, beer, beef, and fowl appear in the hieroglyphs on this limestone offering table belonging to a man names Idnu (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, 54-33-3).

Figure 18: One of a pair of wine jars belonging to a woman named Menedjem. The inscription lists her name and the type of wine (image courtesy of the Penn Museum, E14368 A,B.

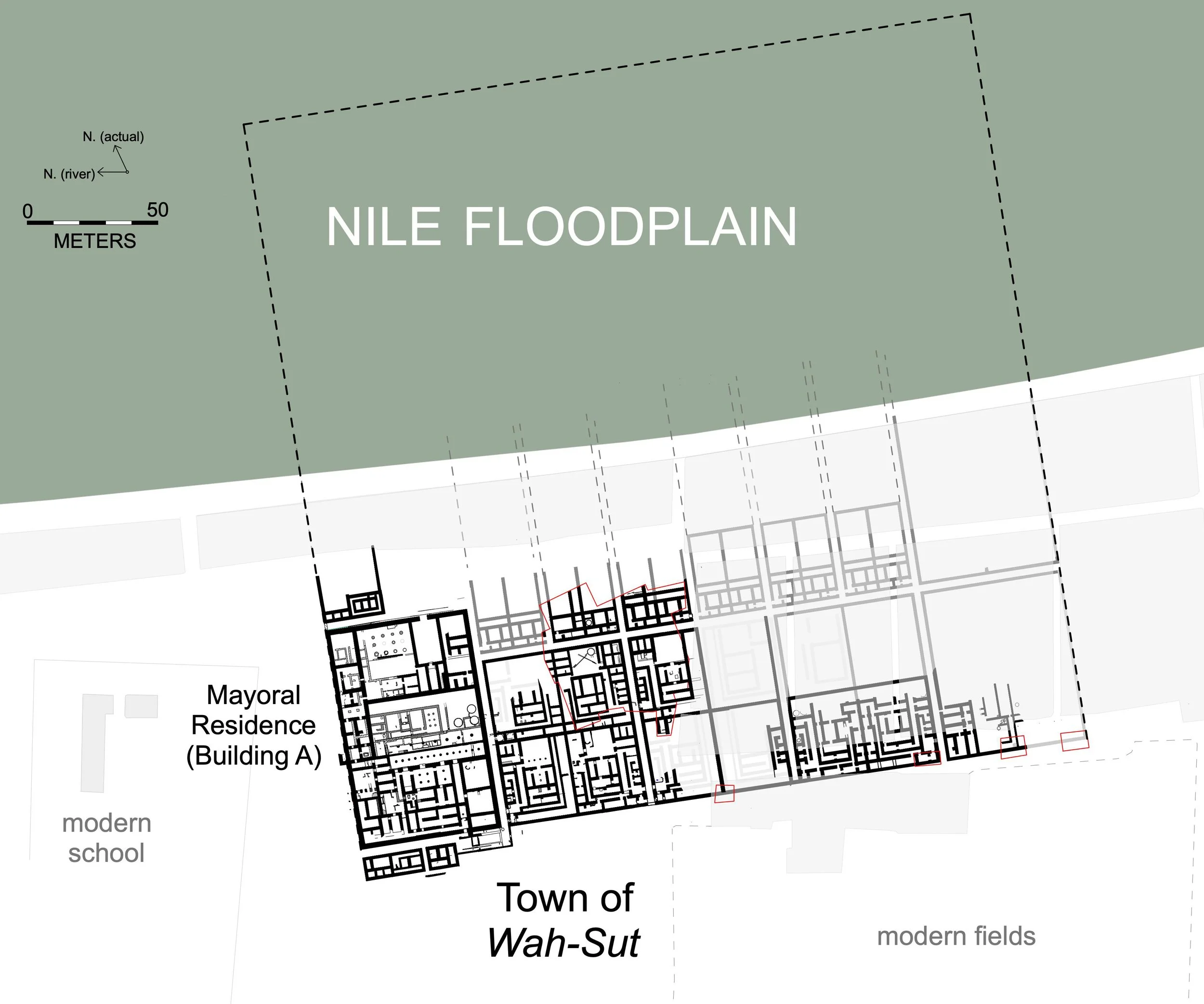

One aspect of ancient Egyptian life that is often overlooked is the nature of their settlements. While much attention is given to the grand temples and beautifully decorated tombs that survive, far less focus has been placed on the villages, towns, and cities that once lined the banks of the Nile. This imbalance is largely due to preservation issues. Most settlements were built along the river’s narrow floodplain, where houses constructed primarily from mudbrick have not endured as well as stone monuments. Because communities were often rebuilt in the same areas over thousands of years, evidence of these ancient towns has been lost to erosion and later construction. This is not to say that we have no evidence of what ancient Egyptian cities and towns may have been like. There have been excavations of towns at sites like Amarna, Kahun, Deir el-Medina, and the recent work at Abydos done by the Penn Museum under the direction of Josef Wegner (Figure 19). All this fieldwork has uncovered individual houses, blocks of housing, or even whole neighborhoods, allowing us to reconstruct what some ancient Egyptian houses looked like.

Figure 19: Excavations at the ancient town of Wah-sut at Abydos have uncovered a Mayoral Residence and smaller adjacent houses.

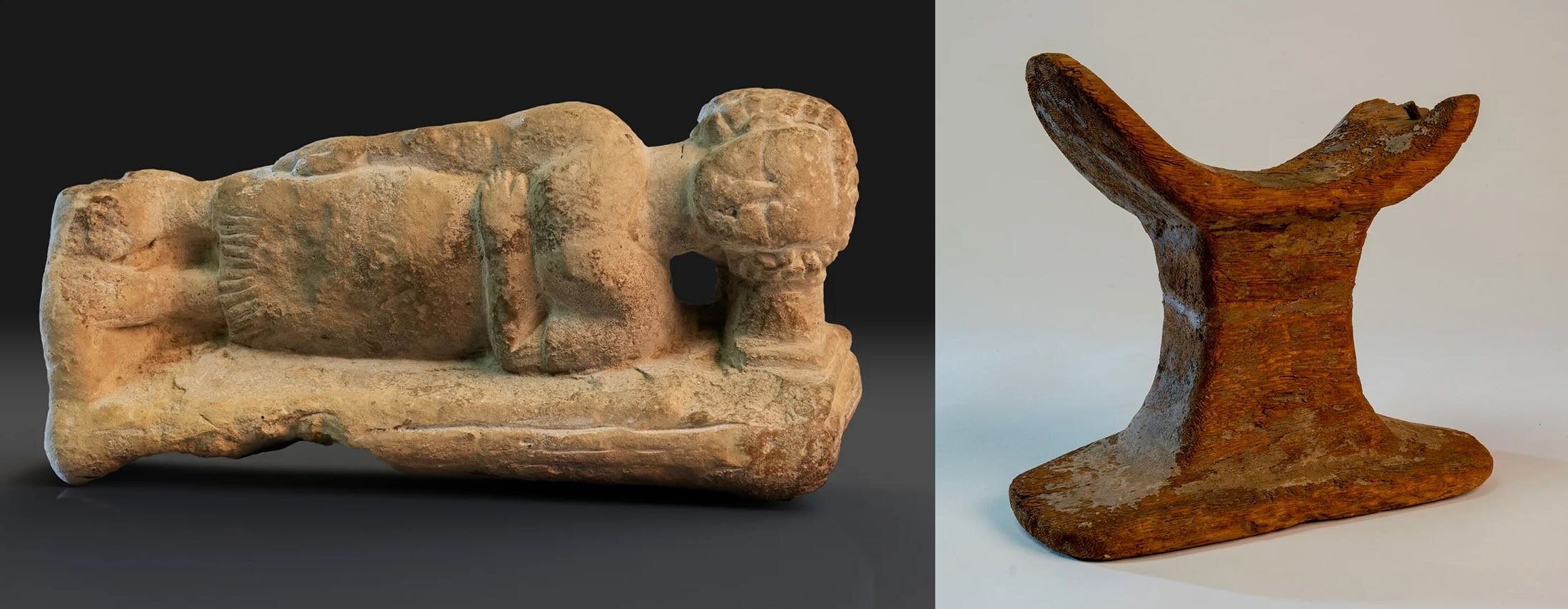

As for the question of furnishings in these houses, we can turn to discoveries like that of the tomb of Kha and Merit which contained a variety of furniture, storage boxes, and baskets where personal items would have been kept. Furniture was simple in form and usually made of wood or stone. The main furnishings in a house included chairs, stools, tables, mats, and beds with headrests for sleeping. Additional information about household furnishings can be seen in small models or figurines depicting such items (Figures 20a–b). Representations of various kinds of furniture can also be seen on tomb walls or on tomb stela; for example, note the chairs used by Tepemankh, Ineb and his wife, and Maienhekau and his family on their funerary monuments. Notably, the legs of many of these chairs are carved in the form of animal legs, a distinctive decorative feature (Figures 21a–b).

Figures 20a–b: This small limestone figure (E1219) depicts a woman sleeping on a bed, using a headrest. An Egyptian headrest (E1149) is on the right. For more information about ancient Egyptian headrests, see the article in Glencairn Museum News.

Figure 21a: The chairs of Ineb and Henti (E1151).

Figure 21b: The chairs on the stela of Maienhekau (E1266).

One might also wonder what types of things the Egyptians did for recreation. One pastime was playing board games (Figure 22); the ancient Egyptians played at least four distinct types. The best-known game was senet, a game for two players played on a board with 30 squares. The goal of the game was to remove all of one’s pieces from the board first by blocking and leaping over the other player’s pieces. The game symbolically alluded to the passage into the afterlife.

Figure 22: This restored wooden senet gameboard has faience game pieces (image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 01.4.1a, gift of Egypt Exploration Fund, 1901).

Another key aspect of daily life was a person’s occupation. Information about the professions and titles individuals held can be found in inscriptions on funerary stelae and tomb walls. Artifacts such as scribal palettes, brushes, and pens, as well as woodworking tools and farming or fishing equipment, also provide insight into the kinds of work people performed. Some women served as priestesses, holding roles such as chantresses or musicians within the temple. An example of a rattle-like instrument called a sistrum can be seen in the gallery. When shaken, it produced a sound that may have calmed the gods or scared away evil forces (Figure 23).

Figure 23: A bronze sistrum rattle in the Glencairn Museum collection (E1269).

Further insights into daily life in ancient Egypt can be gleaned from the wall decorations found in tombs. At certain times, a genre known as “daily life scenes” became popular, depicting activities such as farming, fishing, and craft production. Other valuable information comes from painted wooden tomb models, which appear in burials from the late Old Kingdom through the late Middle Kingdom (Figures 24a–b). These models were intended to provide the deceased with a means of sustenance in the afterlife and commonly represent boats, food preparation, granaries, and various workshops, including those for linen production.

Figure 24a: The Middle Kingdom tomb of Meketre contained many painted wooden models. Here is a model granary showing scribes recording amounts of grain (20.3.11) (image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1920).

Figure 24b: A model ship (20.3.1) from the Middle Kingdom tomb of Meketre (image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1920).

Religious beliefs and practices permeated every aspect of daily life in ancient Egypt, shaping how people lived, worked, and understood the world around them. While formal rituals and ceremonies were conducted in temples by the king and high-ranking priests, most Egyptians expressed devotion on a more personal level within the home. Many households included small shrines dedicated to household deities, and ancestors were also venerated. Religion, magic, and medicine were closely connected. Healing often involved amulets, figurines, and the recitation of spells or prayers intended to restore health or resolve personal troubles. Among Egypt’s vast pantheon, certain deities such as Hathor, Bastet, Taweret, and Bes were especially popular for matters of love, fertility, and protection of the home. Egyptians could present small statues of gods at shrines or temples, either to seek divine aid or to give thanks when their prayers were answered. The Glencairn Museum collection includes examples of these types of statuettes (Figure 25).

Figure 25: Bronze figurines of deities in the Egyptian gallery at Glencairn Museum.

In examining the daily lives of the ancient Egyptians, we can gain a better understanding of the people behind the monuments from the tools they used, to the food they ate, and the deities they worshiped. For the Egyptians, there was no sharp divide between life and the afterlife; rather, existence was seen as a continuous cycle. The material remains that survive, both humble household goods and exquisite works of art, allow us to appreciate the humanity of this ancient civilization and to see how their daily life was inextricably bound to their wish for eternal life.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

Bibliography

David, A. (2003). Handbook to life in ancient Egypt. Revised edition. New York: Facts On File.

David, A. Rosalie and Campbell Price. A year in the life of ancient Egypt. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Archaeology, 2015.

Ikram, Salima 2023. “All good things on the study of ancient Egyptian food and drink.” In Dorry, Mennat-Allah El (ed.), Food and drink in Egypt and Sudan: selected studies in archaeology, culture, and history, 7-19. Le Caire: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw; Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

Killen, Geoffrey 1994. Egyptian woodworking and furniture. Shire Egyptology 21. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Meskell, Lynn (1998). "Intimate Archaeologies: The Case of Kha and Merit". World Archaeology. 29 (3): 363–379.

Sabbahy, L. (2022). Daily life of women in ancient Egypt. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood.

Tooley, Angela M. J. 1995. Egyptian models and scenes. Shire Egyptology 22. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Tyldesley, Joyce 2007. Egyptian games and sports. Shire Egyptology 29. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Uphill, Eric P. 1988. Egyptian towns and cities. Shire Egyptology 8. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Wegner, Josef W. 2024. Wah-Sut: a Middle Kingdom town. Expedition65 (4), 28–34.

Wegner, Josef 2014. The palatial residence of Wah-sut. Expedition 56 (1), 24–31.

Wilson, Hilary 1988. Egyptian food and drink. Shire Egyptology 9. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.