Glencairn Museum News | Number 4, 2025

The staircase between Glencairn’s third and fourth floors features a series of cast-concrete birds that recreate ten plates from John James Audubon’s landmark book Birds of America.

As visitors ascend the main staircase of Glencairn, they will see the railing change from carved teakwood to painted wood, and the steps from teakwood to poured concrete when they reach the set of stairs between the third and fourth floors. As they pause before continuing their climb, they will meet with a series of birds, cast in concrete, running up the side of the staircase. It has long been known that these birds were inspired by the prints of John James Audubon (1785–1851), but only recently has their exact relationship to his work Birds of America been carefully studied. Birds of America (1827–1838) was a landmark work that documented 435 North American birds through life-sized watercolor paintings. Combining scientific observation with skilled artistry, it was an important achievement in both art and ornithology.

E. Bruce Glenn, Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn’s nephew, described these cast-concrete birds as “a series of birds taken from Audubon and beautifully detailed by the use of ground mosaic” (Glencairn: The Story of a Home, p. 64). Raymond Pitcairn himself also credited Audubon; while talking to a group visiting Glencairn, he pointed out the birds and their subtle coloring in the cast concrete, noting that “this is powdered mosaic glass and the Audubon book of birds was our inspiration.” This occurred during the 1965 visit of James Rorimer, then-director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rorimer, accompanied by several members of The Cloisters staff, had come for a tour and lunch at Glencairn, and Pitcairn recorded the discussions throughout the day.

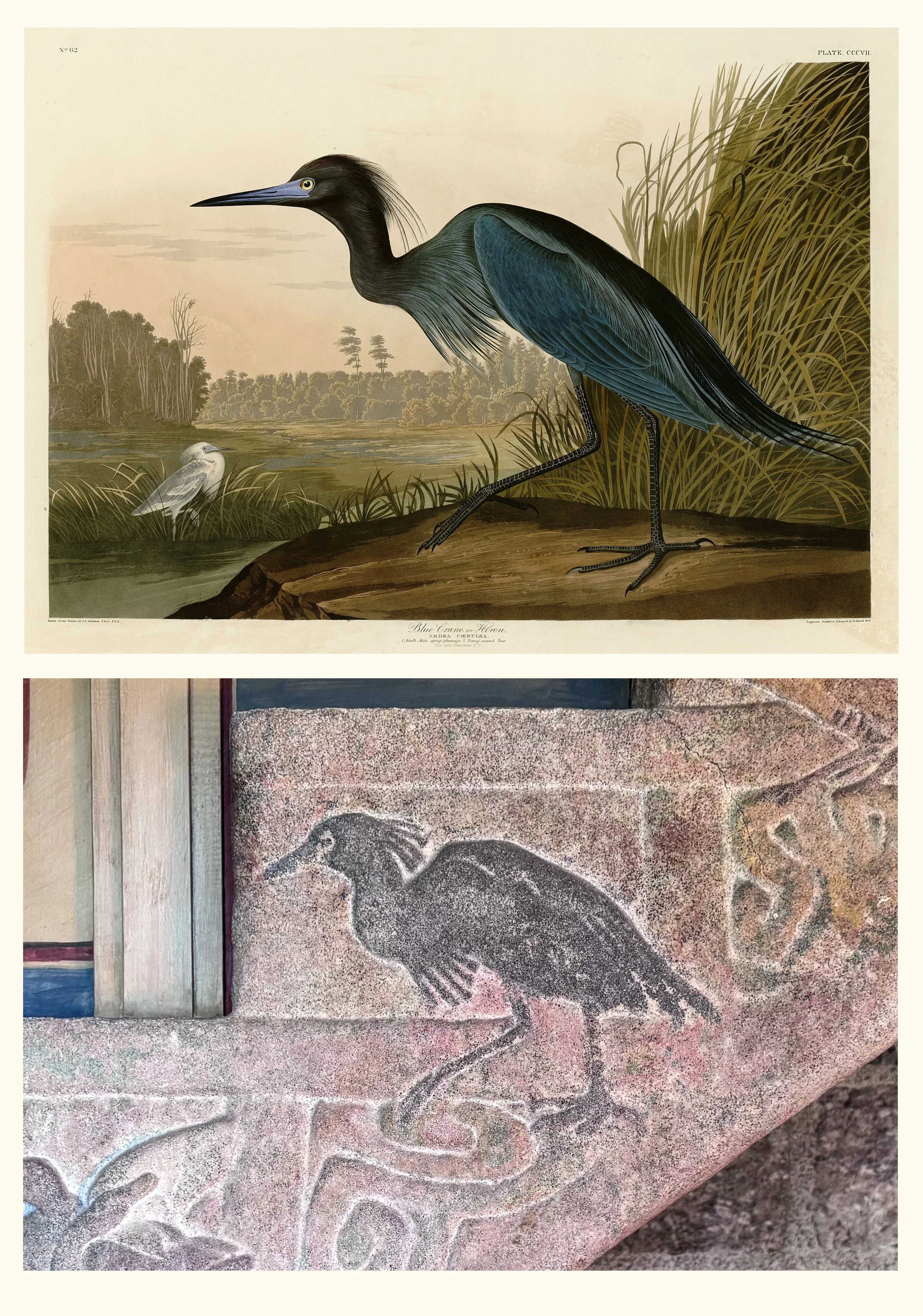

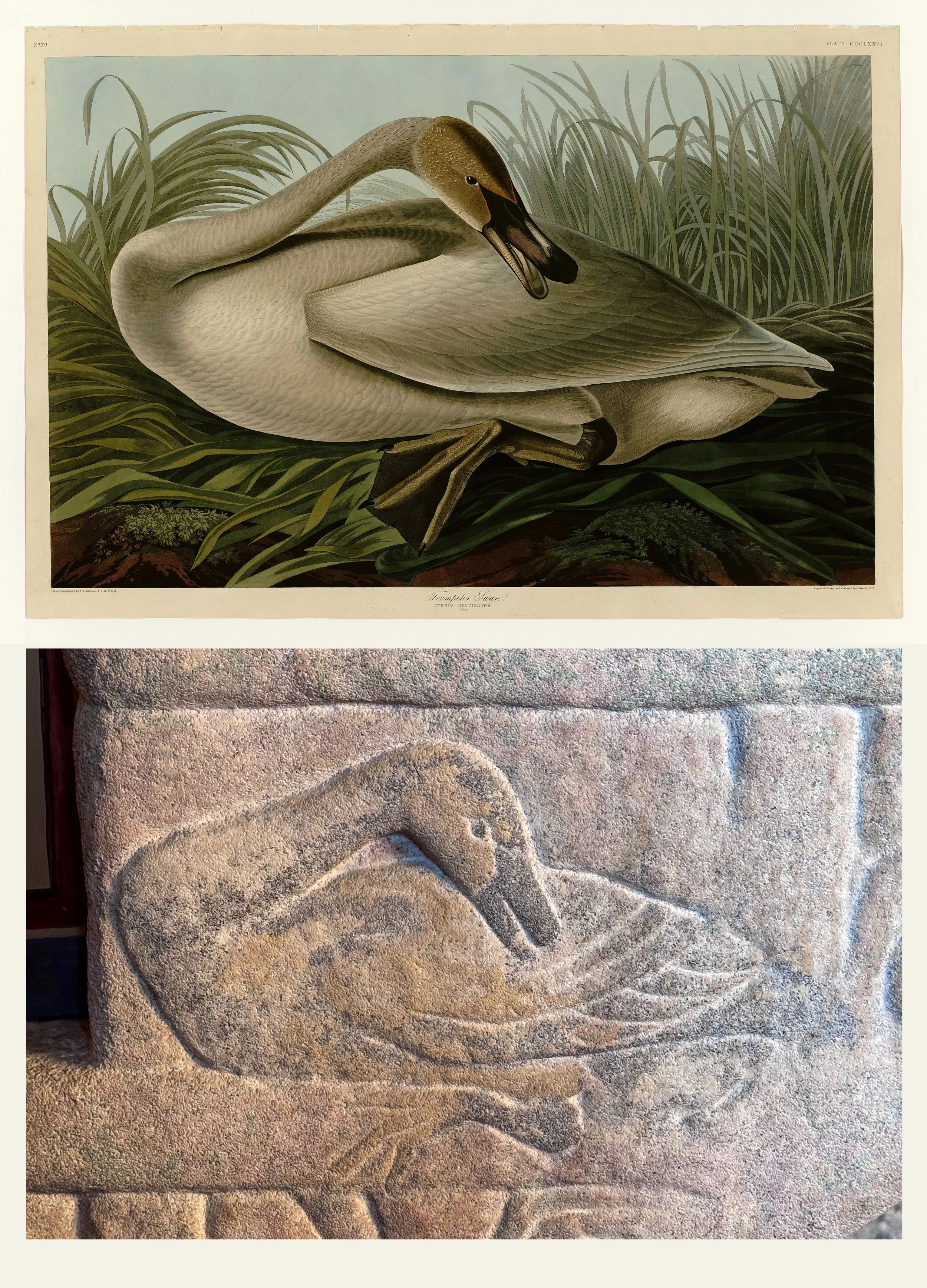

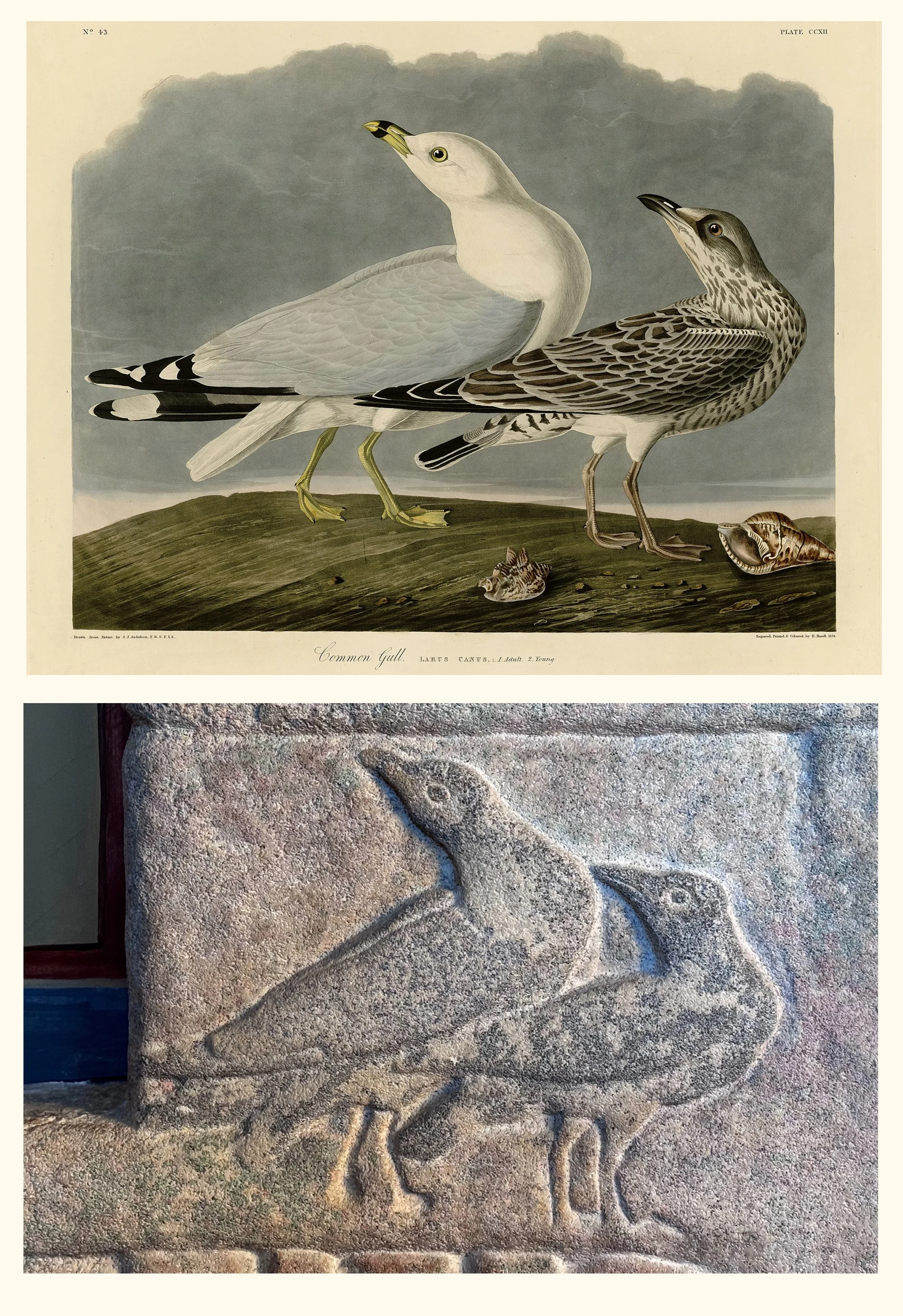

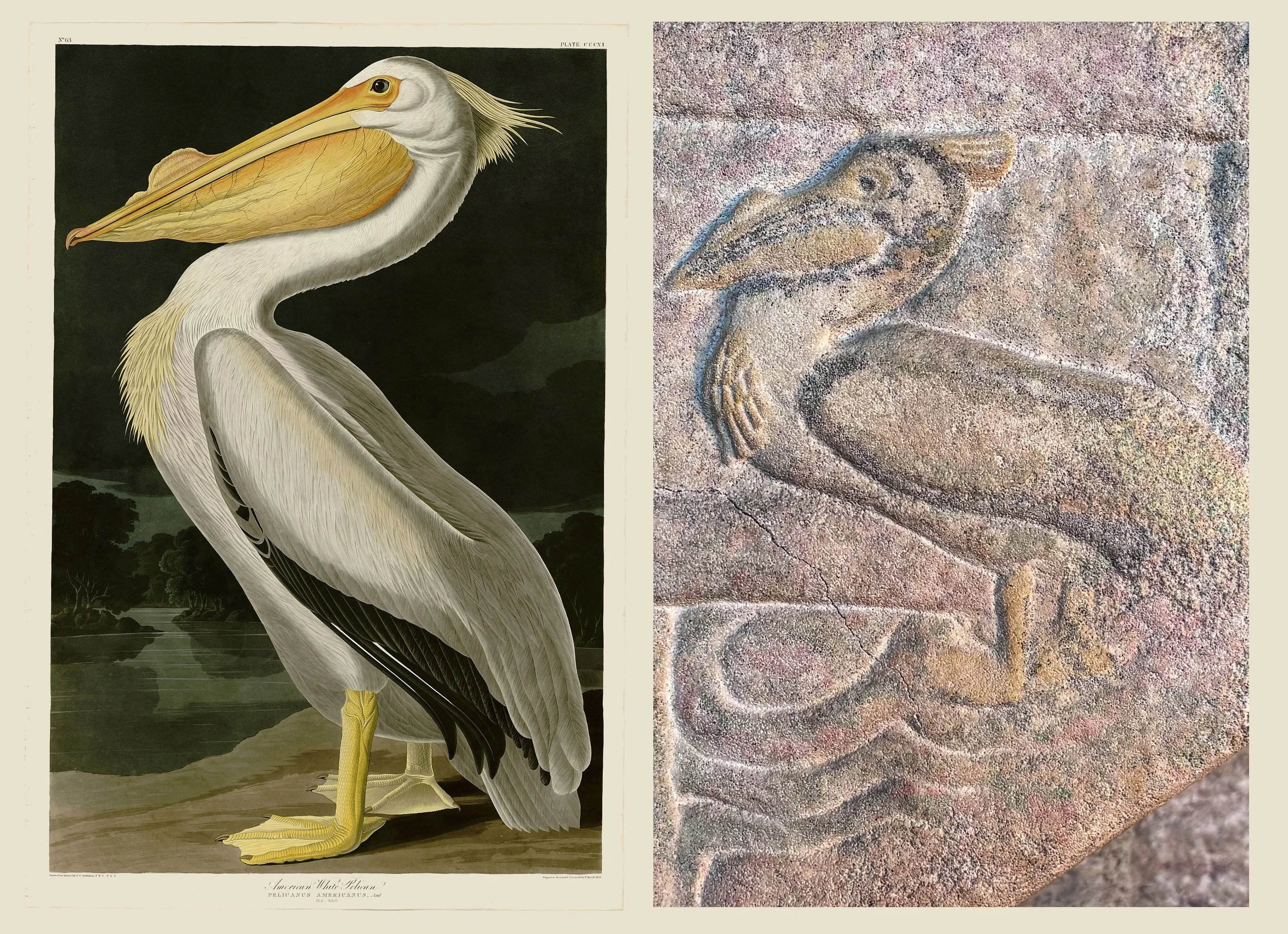

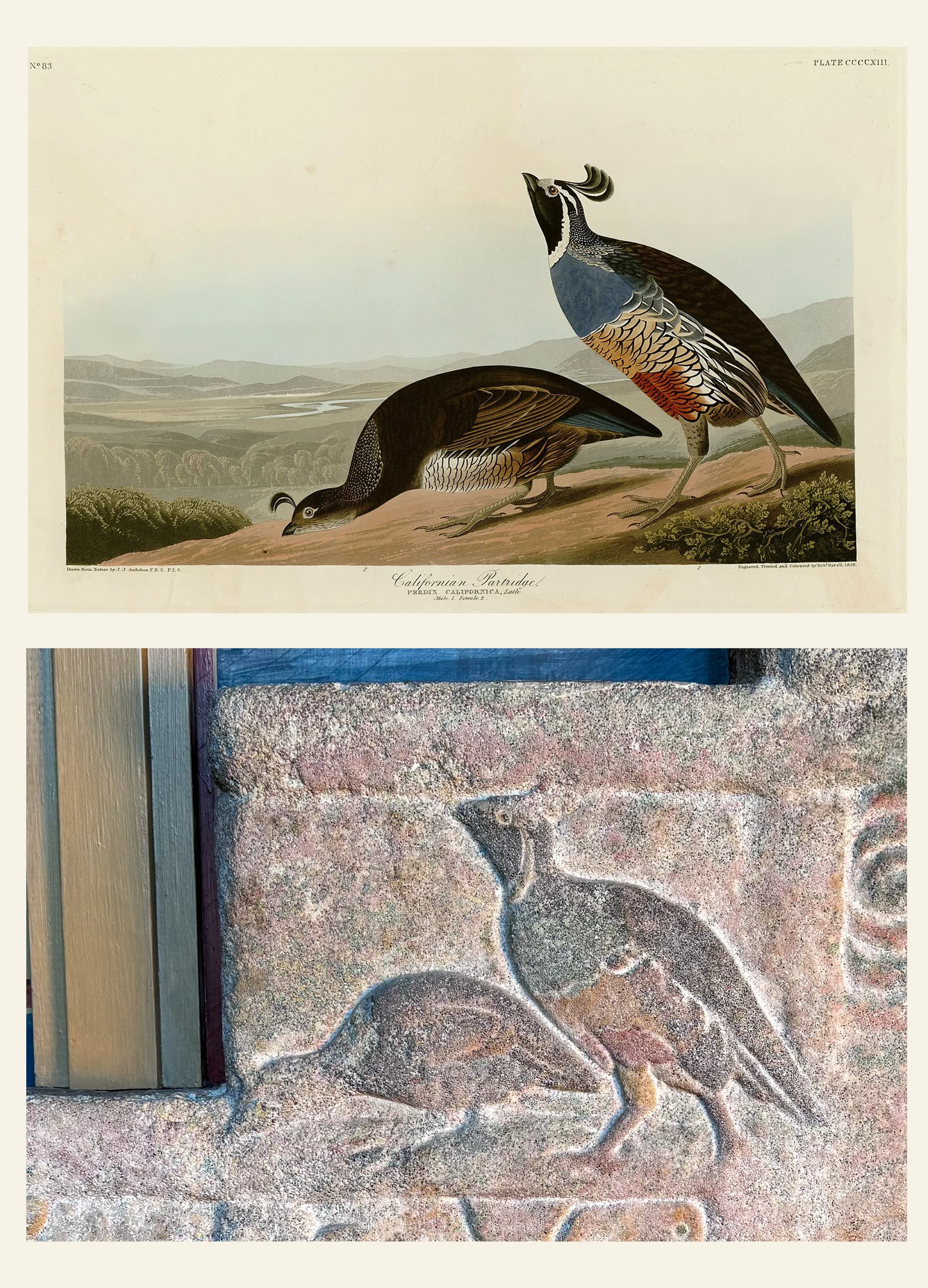

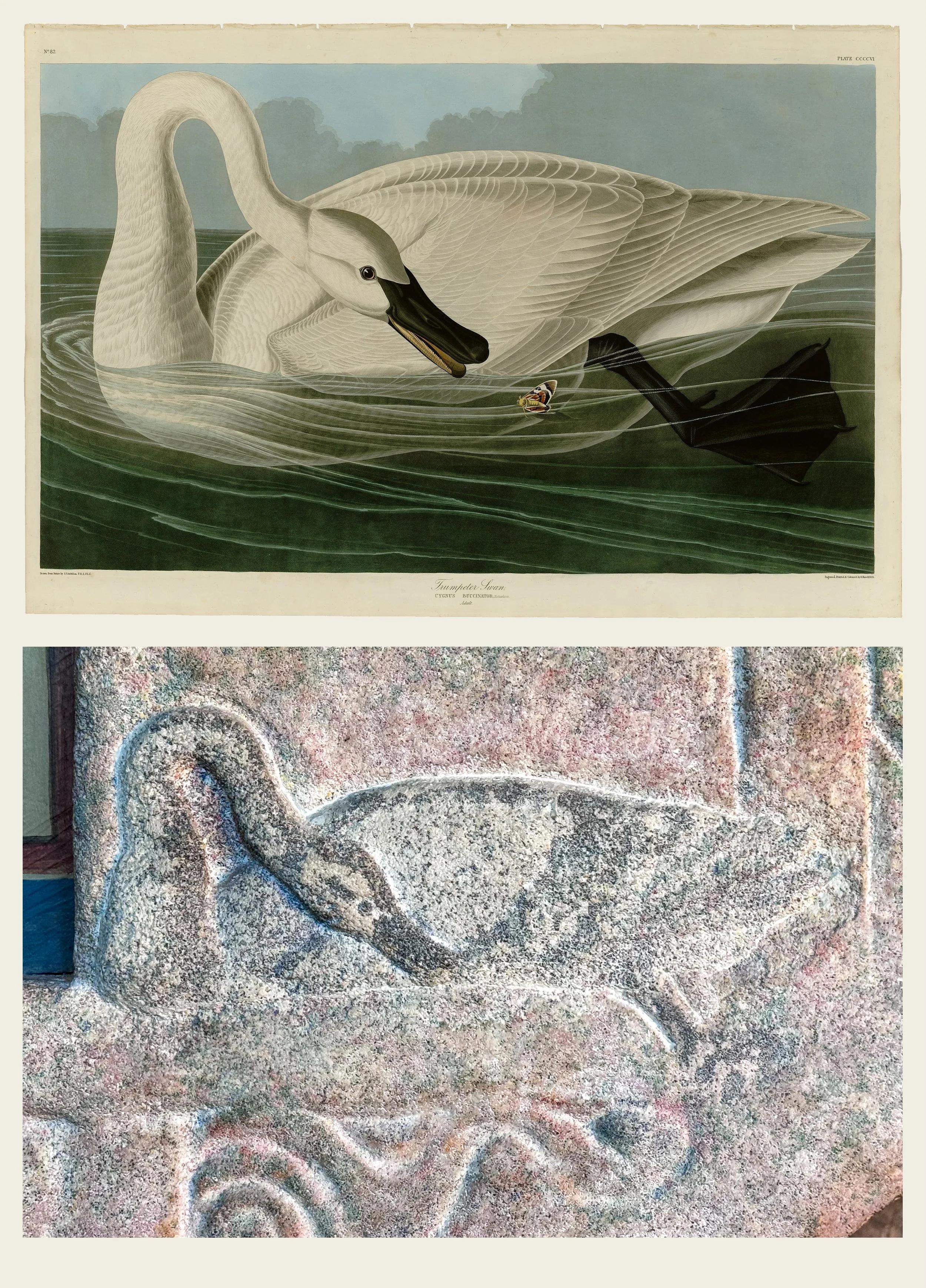

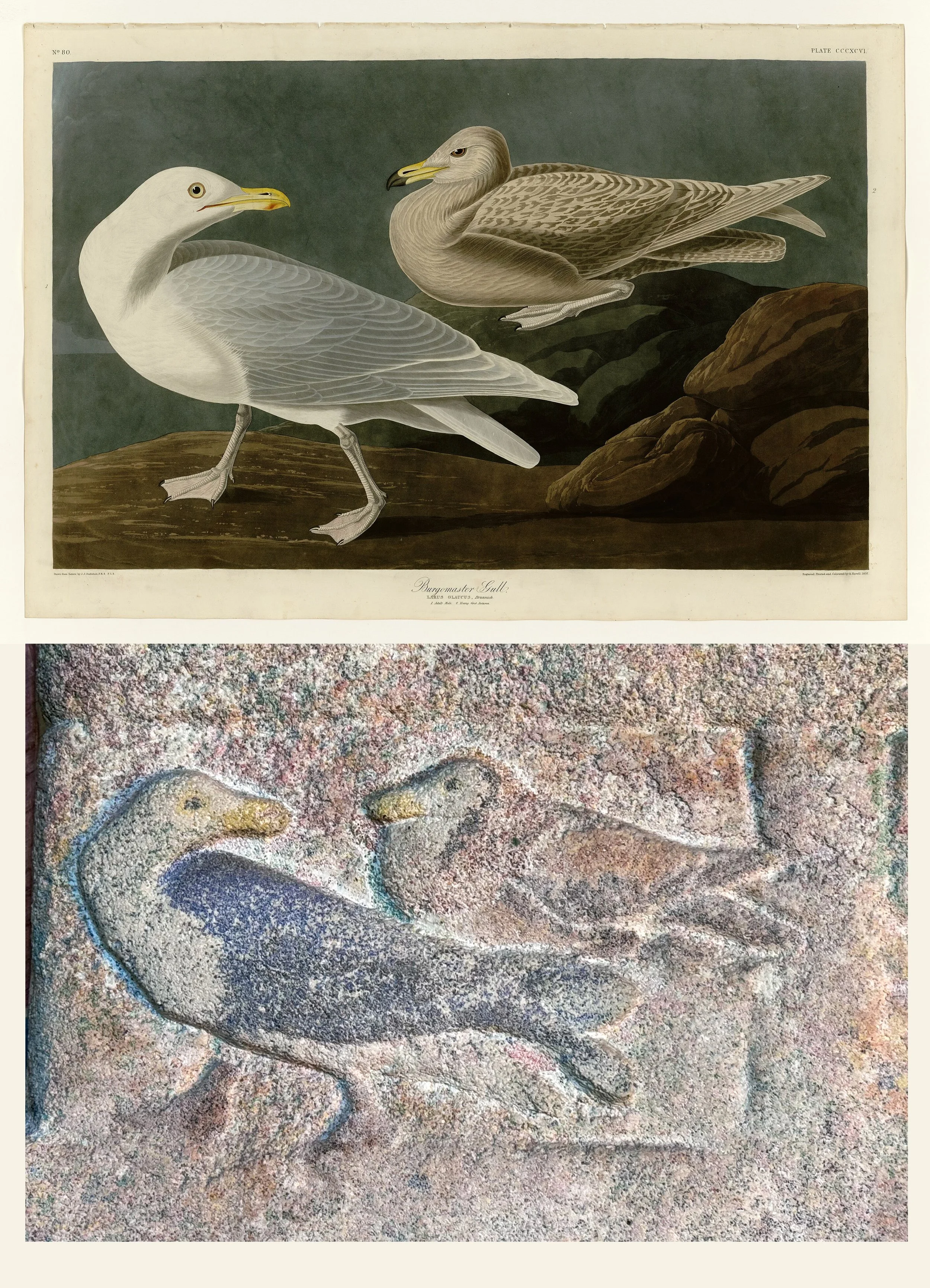

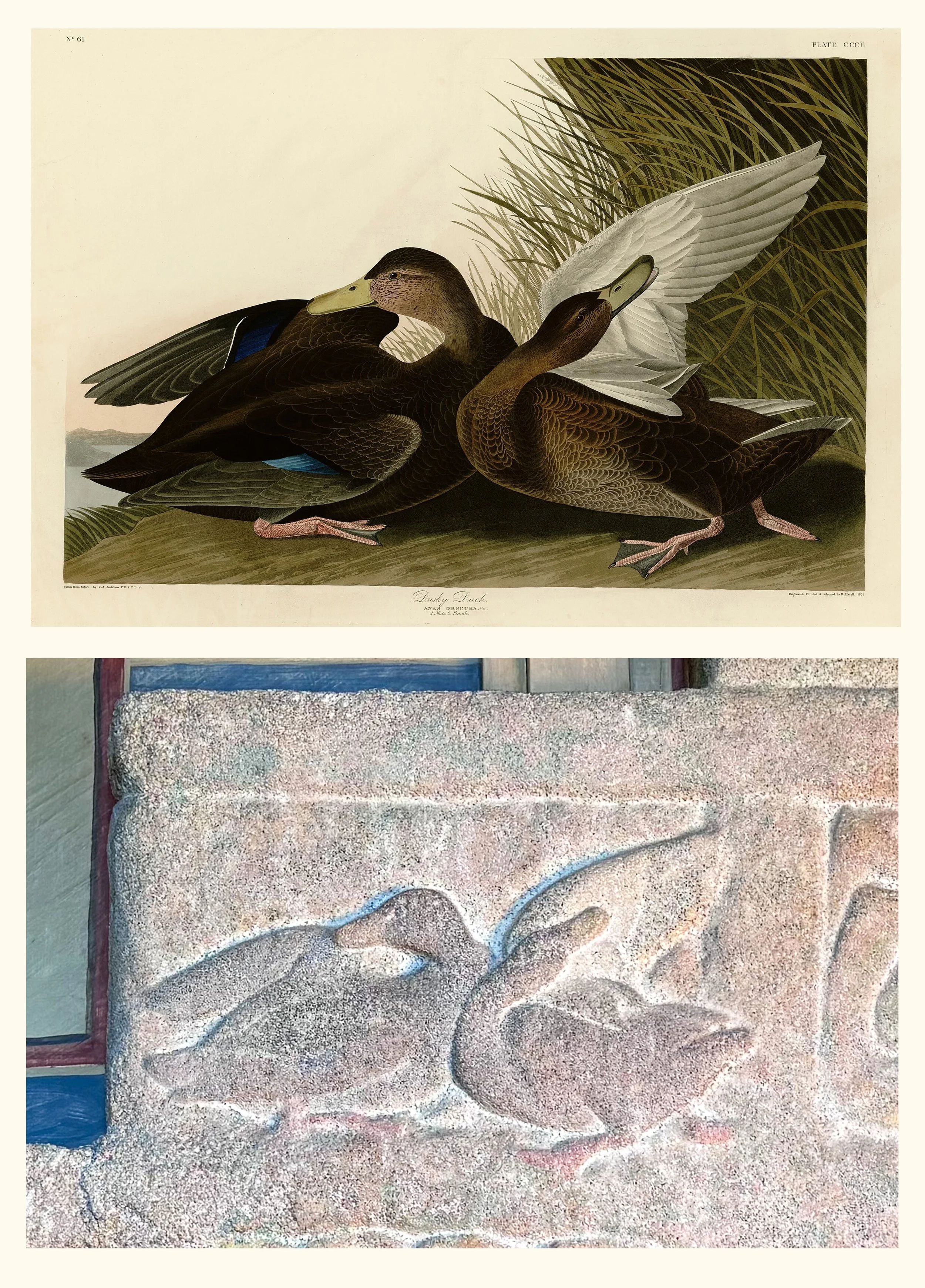

To understand how closely Audubon’s Birds of America influenced the cast birds, it was first necessary to document all the different scenes. Ten distinct bird scenes were identified on the staircase, seven of which are repeated. It was then a matter of combing through the Audubon plates to find possible matches. Because Audubon’s watercolor paintings are so detailed, documenting every placement of the feet, turn of the neck, and stretch of the wing, it was possible—and very exciting—to find matches. All ten of the scenes on the staircase have been successfully matched to the corresponding Audubon plates. A digital pairing of the plates and photographs of the concrete birds reveals a remarkable fidelity on the part of Pitcairn’s artists (see Figures 1–10).

The order of the ten adapted Audubon plates, going from the bottom of the staircase on the third floor toward the fourth floor, is listed below. The titles of the birds and descriptions are taken from Audubon, but modern names of the birds are also given if they differ. The accompanying photographs (Figures 1–10) follow the same order as this list:

Audubon Plate 307, Blue Crane or Heron (adult male, spring plumage); Little Blue Heron (modern name)

Audubon Plate 204, Salt Water Marsh Hen (adult male, spring plumage, right; female, left); Clapper Rail (modern name)

Audubon Plate 376, Trumpeter Swan (young)

Audubon Plate 212, Common Gull (adult, left; young, right); Ring-billed Gull (modern name)

Audubon Plate 311, American White Pelican (adult male)

Audubon Plate 413, Californian Partridge (male, right; female, left); California Quail (modern name)

Audubon Plate 406, Trumpeter Swan (adult)

Audubon Plate 396, Burgomaster Gull (adult male, left; young, first autumn, right); Glaucous Gull (modern name)

Audubon Plate 257, Double-crested Cormorant (adult male, spring plumage)

Audubon Plate 302, Dusky Duck (adult male, left; female, right); American Black Duck (modern name)

Figure 1: Audubon, Blue Crane or Heron, 1836. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2: Audubon, Salt Water Marsh Hen, 1834. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3: Audubon, Trumpeter Swan, 1837. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4: Audubon, Common Gull, 1834. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5: Audubon, American White Pelican, 1836. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 6: Audubon, Californian Partridge, 1838. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 7: Audubon, Trumpeter Swan, 1838. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8: Audubon, Burgomaster Gull, 1837. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 9: Audubon, Double-crested Cormorant, 1835. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 10: Audubon, Dusky Duck, 1836. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

After the first ten distinct bird plates, seven additional birds going up the staircase are repeats. Figures 1–3 appear again, and then the design skips over Figures 4–5 to finish up with a repeat of Figures 6–9.

It is well known that the Pitcairn family loved birds. The family’s dining area in the Upper Hall was located beside a large south-facing window, and they placed bird feeders outside the window that could be easily viewed during meals. Mildred, in particular, passed on her love of birds to both her children and grandchildren, using bird identification cards to teach them the birds’ names (Figure 11). Two of her granddaughters recently shared their happy memories of these cards. They would sit beside Mildred during this game, and if they didn’t guess the name of the bird, their grandmother would tell them. But if no one knew the name, the joke was that “the cat got it.”

Figure 11: Mildred Pitcairn shared her enthusiasm for birds with her children and grandchildren. She used these National Audubon Society bird identification cards, now in the Glencairn Museum collection, to teach them the birds’ names.

Glencairn has many examples of the innovative use of concrete throughout the building. Molds, powdered mosaic glass incorporated into the concrete mix, and even decorative painting on the surfaces were sometimes used to produce the effects Raymond Pitcairn wanted. In 1931, he wrote to an employee of Pittsburgh Plate Glass, the business his family had co-founded: “My belief is that the field for modern decoration applied to modern ferro-concrete architecture is unlimited. If permanent mural decoration of high quality done by real artists can be achieved, concrete will come into its own for better grade buildings” (Glencairn: The Story of a Home, p. 63).

The bird staircase in Glencairn is a singular example of Raymond Pitcairn’s desire to use concrete in new and exciting ways. It also must have brought daily enjoyment to a family who loved birds and bird watching. Be sure to take a closer look next time you are on Glencairn’s third floor.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.