Glencairn Museum News | Number 7, 2012

Black granite Egyptian libation bowl, circa 1350 BC.

The Egyptian gallery has long been a favorite with visitors to Glencairn Museum. Ancient objects in the gallery are organized around religious themes such as Egyptian Gods, Egyptian Mythology, and Mummy Magic, with miniaturized dioramas bringing the ancient beliefs to life. Research is ongoing into the history of this small but important collection, which had its beginnings in the 19th century. A full-length article, “From Parlor to Castle: The Egyptian Collection at Glencairn Museum,” has recently been made available on Glencairn’s website (here).

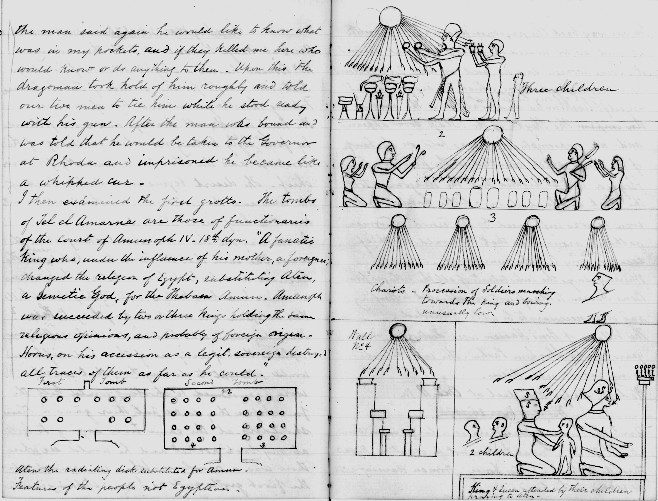

Figure 1: A two-page spread from the travel diary of John Pitcairn, written in 1878 during a trip to Egypt.

2012 marks the 134th year of the Egyptian collection. During the winter and spring of 1878 the Rev. William Henry Benade (1816–1905), a New Church (Swedenborgian) clergyman, and John Pitcairn (1841–1916), a philanthropist and member of Benade’s congregation, spent three months on the Nile. They travelled in a dahabiyah, a traditional Egyptian houseboat, and Pitcairn purchased a number of small Egyptian antiquities. This marked the beginning of a museum for the Academy of the New Church, the Christian school the two men had recently founded in Philadelphia.

Figure 2: Shabtis (funerary statuettes) from the collection of Rodolfo Vittorio Lanzone (1834–1907).

Later that year Benade wrote to Pitcairn from Italy, asking if he would be willing to purchase a collection of Egyptian antiquities from Rodolfo Vittorio Lanzone (1834–1907), an Egyptologist at the Turin Museum. Benade intended to use these artifacts to teach Egyptian religion and mythology to students at the Academy in Philadelphia. The Lanzone collection includes bronze statuettes of gods and goddesses and a large collection of magical amulets (Figure 2). Pitcairn agreed, and by the end of 1878 over 1,000 objects had been shipped to the school in Philadelphia.

Figure 3: Bishop William Henry Benade (1816–1905).

Benade returned home from his journeys in August of 1879, taking up residence at 110 Friedlander Street. At this time he moved a portion of the Egyptian collection into the parlor of the house, which also served as classroom space for the Academy. In November he began a twelve-part lecture series for students and the public on the topic of Egyptian religion, delivered in one of the Academy’s schoolrooms for an admission fee of ten cents per lecture. Benade illustrated his lectures with photographs acquired in Egypt, temple plans, and objects from the Academy’s collection. According to one reporter, “After giving us so much spiritual food, Mr. Benade showed us some material food in the form of Egyptian bread, probably thousands of years old. But nobody present seemed to care to taste it” (Morning Light: A New-Church Weekly Journal, March, 1880, 37 ff.).

Over the next several decades the museum traveled with the school as it moved from place to place in Philadelphia. In 1897 the Academy moved to a new campus in nearby Bryn Athyn, a New Church community in the countryside. The museum’s holdings were initially given a room on the first floor of the main academic building, but were later transferred to the top floor of a building financed by John Pitcairn to house both the library and museum. Finally, in the early 1980s the museum’s collections were moved to Glencairn, the former home of Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn, where they merged with the Pitcairn collections to create what is now known as Glencairn Museum.

Figure 4: Egyptian Gallery on the fourth floor of Glencairn Museum.

Raymond Pitcairn, the son of John, had taken ancient history courses at the Academy, where he would have become familiar with the Egyptian collection purchased by his father for the school. Raymond is best known internationally as a collector of medieval art, and as a Christian he was inspired by the biblical imagery in the medieval works he collected. But as a member of the New Church, Pitcairn was also intrigued by Emanuel Swedenborg’s teaching that God was actively present in even the most ancient religions. According to Swedenborg, the monuments of the ancient Egyptians were a sincere and inspiring attempt to connect with the one true God who has been accessible to all people throughout history. Pitcairn’s collecting interests broadened from medieval art to include art from ancient Egypt, the ancient Near East, ancient Greece and Rome, and a few objects from Asian and Islamic cultures.

Figure 5: The “spirit door” from the 5th Dynasty tomb of Tep-em-ankh.

Most of the larger Egyptian objects in Glencairn Museum’s collection were purchased in the 1920s by Raymond Pitcairn from dealers in New York City. Several have received international attention, such as the 4,400-year-old Egyptian “spirit door,” from the 5th Dynasty tomb of Tep-em-ankh in the western cemetery of the Great Pyramid of King Khufu. Last year Tep-em-ankh’s door went on loan to the Roemer- und Pelizaeus- Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, where it was part of a major international exhibition, “Giza: Gateway to the Pyramids.” (Read more about this exhibition.)

“From Parlor to Castle: The Egyptian Collection at Glencairn Museum,” is available here.

(CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.