Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2016

Glencairn’s Syro-Hittite siren cauldron attachment from the 8th Century B.C.

Soon after the remarkable gift in 1980 from the family of Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn to the Academy of the New Church of their home, Glencairn, for a museum, the newly appointed Director, the Reverend Martin Pryke (1914-1996), began the task of documenting the combined collections of the Academy and those acquired by Raymond Pitcairn. Many of these works of art and archaeological artifacts had never been catalogued, photographed, studied, or published, beyond that written by Pitcairn himself; thus Rev. Pryke began looking for scholars who might assist with the daunting but thrilling job of cataloguing the diverse collections.

In 1981 David Gilman Romano, a newly minted Ph.D. in Classical Archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania, was hired to identify which objects in Glencairn belonged to the world of ancient Greece, Rome, Etruria, and related cultures, assign catalogue numbers to them, and write catalogue descriptions, including dating them and citing comparable objects. Some 500 Classical objects were identified—of stone sculpture, bronzes, terracotta figurines, bone and ivory objects, pottery, lamps, coins, and jewelry—and the job of completing the catalogue took many years, with the help of more than 75 international scholars who were invited to visit Glencairn or were gracious enough to assist with information from photographs sent to them. David Romano combined forces in this task with Dr. Irene Bald Romano, who had also received her Ph.D. from Penn in Classical Archaeology. Both of them were employed at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology beginning in 1981-1982, so the completion of the catalogue occurred between their other teaching, administrative, and curatorial duties at Penn. With the research of David and Irene Romano to guide the staff, Glencairn’s first Greek Gallery opened in December of 1996, followed by a Roman and Early Christian Gallery in April of 2001. Together the Romanos published a major scholarly catalogue of the Classical collections in 1999 (Catalogue of the Classical Collections of the Glencairn Museum), bringing this part of Glencairn’s holdings to the attention of scholars around the world.

David Romano recalls his very first day at Glencairn in the fall of 1981, when Rev. Pryke was introducing him to the building and the collection. David stopped dead in his tracks when he spotted a most unusual bronze object being used as a doorstop in the former bedroom of the brothers Garth and Lachlan Pitcairn, which had been turned into the storage room for part of the ancient collection. The object was thought to have been originally a flag pole finial. Having been trained at Penn where graduate students since the 1950s regularly participated in excavations and research led by Rodney S. Young (1907-1974), and later by other Penn archaeologists, at the Phrygian capital of Gordion in central Turkey, David immediately recognized that the heavy bronze object was no flag pole finial but a somewhat rare attachment for a cauldron of a type found in the so-called Midas Tumulus at Gordion. Though strictly speaking outside the purview of scholars of the Classical world, this cauldron attachment couldn’t have been in a better place to receive the best possible scholarly treatment.

Now, some 35 years after that discovery within the halls of Glencairn, bronze cauldrons, including one with siren cauldron attachments similar to the one in Glencairn, and other artifacts from Gordion have come to Philadelphia and are on display in a special exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, The Golden Age of King Midas (February 13-November 27, 2016; Figure 1).

Figure 1: View of Penn Museum’s exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, March 2016. Photograph by Ed Gyllenhaal, with permission of Penn Museum.

Glencairn’s Siren Cauldron Attachment

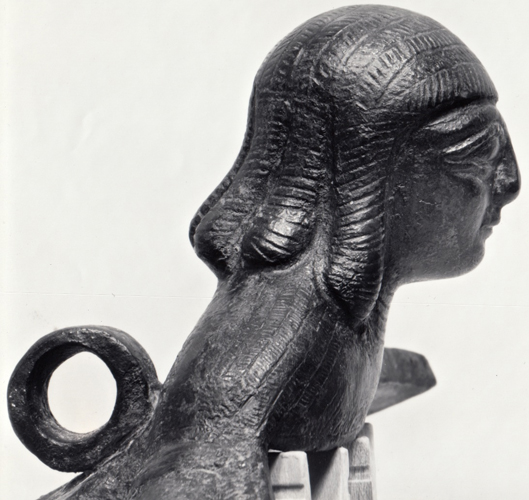

Among Glencairn’s varied collections from the ancient world, this bronze cauldron attachment stands out for its rarity. It is unclear why Raymond Pitcairn would have found this object of interest when he bought it in November of 1925 from Dorlacher Brothers, dealers in London and New York, who identified it as an “Assyrian bronze bird.” Syro-Hittite or Neo-Hittite is a more accurate designation, and more than a bird, the artifact represents a Near Eastern mythological creature with the head, bust, and arms of a human, and the outstretched wings and tail of a bird. In antiquity it was attached to the rim of a large open vessel to hold a lifting ring.

The Glencairn cauldron attachment (05.SP.28) measures 0.199 meters in length, 0.289 meters in width at the wings, and weighs a hefty 2.52 kilograms, solid cast from a mould (Figures 2a-d).1 Analysis conducted in the 1980s by the MASCA Laboratory at the Penn Museum shows that the metal is a copper alloy with around 10% tin and substantial amounts of arsenic, antimony, iron, and zinc impurities.2 When polished and before it had aged to its natural dark-green patina, the cauldron attachment would have gleamed like gold.

Figures 2a-d: Glencairn siren cauldron attachment. Photographs from David Gilman Romano and Irene Bald Romano, Catalogue of the Classical Collections of the Glencairn Museum (Bryn Athyn, 1999), 47-48.

It is in an excellent state of preservation, with rivets preserved in each wing and in the tail for its attachment to the rim of the cauldron. A cast ring on the back for attaching a loose lifting ring, now missing, is flanked by triangular openings. The human bust has a round head with wig-like hair divided into seven thick, crosshatched tresses brushing the top of the shoulders. The face is full with large, almond-shaped bulging eyes, a prominent nose, and small mouth. On the front of the torso is a necklace composed of five parallel incisions, and on the chest is a band of six incised, linked triangles. On the wrists and elbows of the outstretched arms are narrow raised bands, perhaps bracelets or armbands. The figure wears a short-sleeved garment, decorated with hatching at the shoulders and at the edge of the sleeves. On the wings and tail is an incised feather pattern. The raised semi-circular band from elbow to elbow is incised with a repeating triangular design (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Incised decoration of Glencairn siren (not to scale). Drawing by Martha Gyllenhaal.

Sirens

Most scholars would identify this figure as female since there are attachments with bearded human-headed winged demons that are certainly male, and attachments of both types are sometimes found on the same cauldron, as in one from the Midas Tumulus at Gordion (MM 3), discussed below. The non-bearded ones, like the one in Glencairn, are called sirens by association with winged creatures of Greek mythology. Sirens were dangerous bird-like females who tempted sailors with their hauntingly beautiful song. In Homer’s Odyssey (XII, 39) Odysseus and his sailors were warned about the lethal consequences of succumbing to the music of the sirens. Odysseus had to be lashed to the mast of his ship, and his sailors filled their ears with beeswax in order to avoid the sirens’ allure (Figure 4). After centuries of transmission by oral tradition, the Homeric epics were written down around the end of the 8th century or beginning of the 7th century B.C. To this same period we can date bronze cauldrons from various parts of the Mediterranean, with attachments representing fantastic, hybrid monsters such as sirens and griffins (body, tail and back legs of a lion combined with the head, wings and talons of an eagle). The meaning of these delightful, scary, or apotropaic devices on cauldrons—the sirens facing inward, peering across the cauldron (Figure 5), and the griffins facing outward—is open to interpretation.3

Figure 4: Attic red-figured stamnos with a scene of Odysseus and the Sirens, ca. 480-470 B.C., from Vulci, British Museum E440. Image in the public domain through Wikipedia.

Figure 5: Cauldron from Tumulus MM, Gordion (MM 3), on loan to Penn Museum from the Museum of Anatolian Civilization, Ankara, Turkey, showing back of a bearded demon attachment, with lifting ring intact. Photograph by Ed Gyllenhaal, with permission of Penn Museum.

Parallels for Glencairn’s Siren Cauldron Attachment

In general, the earliest of such cauldrons with attachments of fantastic creatures were made in the second half of the 8th century B.C and appear in the broader Anatolian and Mediterranean worlds as exotic luxury items. The closest parallel for Glencairn’s siren attachment is one from an 8th century tomb at the Urartian site of Toprakkale, near Lake Van in eastern Turkey, now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.4 It is so close, in fact, that the two may have been made for the same cauldron (Figures 6a-d). Also very close are those attached to two cauldrons from the so-called “Midas Mound” at Gordion in ancient Phrygia, in central Turkey—discovered some 25 years after Raymond Pitcairn’s purchase of Glencairn’s siren attachment. The dating of the Glencairn attachment in the second half of the 8th century B.C. is based on the close dating of the archaeological context of the Gordion examples (Figure 7).

Figures 6a-d: Toprakkale siren cauldron attachment, Istanbul Archaeological Museum, acc. 41. Photographs courtesy of the late Professor Ekrem Akurgal.

Figure 7: Map of Mediterranean and Near East with sites where siren cauldron attachments have been found. Drawing by Julie Cowan in D. G. Romano and V. C. Pigott, “A Bronze Siren Cauldron Attachment from Bryn Athyn,” MASCA Journal 2 (1983), 124.

The Gordion Siren Cauldron Attachments

In addition to a rich array of wooden furniture, textiles, and many ceramic and bronze vessels and bronze fibulae (ancient clothing pins), three large, well-worn bronze cauldrons set on iron tripod stands were found against the south wall of an impressive chamber of juniper, cedar, and pine at Gordion, beneath an earthen tumulus more than 53 meters high—an elaborate burial of an elite ruler of the kingdom of Phrygia (Figure 8).5 One cauldron has bulls’ heads attachments (MM 1); one has two male demons and two siren busts riveted at the rims (MM 3: H. 0.515; Diam. at rim 0.58; Max. Diam. of body 0.782 m; Figure 9); and one has a complete set of four siren attachments (MM 2: H. 0.485; Diam. at rim 0.578; Max. Diam. of body 0.775 m; Figures 10a-c). Rodney S. Young and the excavators of the tomb in the 1950s dubbed it the “Midas Mound” or MM, but Young soon recognized that it was not the burial place of the famous King Midas “with the golden touch” who ruled from ca. 740 to 700 B.C. and whose story is told by the Latin poet Ovid in the 1st century A.D. (Metamorphoses, XI. 85-145),6 but probably that of Midas’s father King Gordios.7 There has been some shifting in the dating of the tomb over the years,8 but the most recent analysis indicates that the tomb was constructed ca. 740 B.C., probably by Midas for his father.9 Chemical residue analysis of various metal vessels from this tomb shows that the feast at the funeral of the Phrygian king included a fermented beverage of grape wine, barley beer, and honey mead that was almost certainly ladled into drinking vessels from the large cauldrons; it was served with a spicy mix of roasted sheep or goat with lentils.10 The Gordion cauldrons themselves were not tested for their contents, but there is enough other evidence from Near Eastern, Greek and Etruscan tomb paintings, painted depictions on vases, and scenes in relief sculpture to feel confident that such large vessels were used for liquid refreshment.

Figure 8: Interior of Tumulus MM, Gordion, with cauldrons against southern wall, 1957. Photograph courtesy of the Gordion Archives, Penn Museum, neg. #G-2381.

Figure 9: Bearded male demon attachment from a bronze cauldron (MM 3) from Tumulus MM, Gordion. Photograph courtesy of the Gordion Archives, Penn Museum, neg. #76449.

Figures 10a-c: Bronze cauldron (MM 2) from Tumulus MM, Gordion, with four siren cauldron attachments. Photographs courtesy of the Gordion Archives, Penn Museum, neg. #G-2409, #102957, #GR-380-038.

We don’t know where the Glencairn example was discovered archaeologically or the exact manufacturing site(s) of such cauldron attachments, but most scholars accept that those of “Oriental” or Near Eastern type were probably made in a Syro-Hittite workshop(s) in south-central Anatolia (Turkey) or North Syria, the region that is embroiled in such terrible conflict today. A comparison of the compositional analysis of the bronze of the Glencairn siren cauldron attachment with those from Gordion shows a close match, so close in fact that they may have been made in the same workshop from the same metal ore source.11 Some have suggested that the Gordion examples may have been manufactured in Phrygia itself, perhaps by Syro-Hittite craftsmen working abroad.12

Greek Cauldrons

An “Orientalizing” development in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. was prevalent in the broader Mediterranean, a vibrant time of exchange when many eastern ideas and art forms entered the Greek and the Etruscan worlds. Similar cauldrons were given as votive gifts to the gods at Panhellenic sanctuary sites, such as Olympia or Delphi, or were deposited as valued items in elite Etruscan tombs in Italy, such as the Bernardini Tomb at Praeneste (modern Palestrina). They evoke the communal feasting that took place on the occasion of aristocratic funerals or religious festivals.

At a site we are excavating in the mountainous region of Arcadia in southern Greece on Mt. Lykaion, miniature cauldrons with tripod legs were deposited over several centuries, possibly beginning in the late 10th century B.C. and continuing in the 7th century B.C., as votives to Zeus in an open-air altar on the peak of the mountain (Figures 11 and 12a-b).13 Although there is no direct association between these tripod cauldrons and the Glencairn type of siren attachment, large tripod cauldrons may have been the prizes given to the victors at the athletic games in honor of Zeus at this sanctuary site. The date of the origin of these Lykaion Games is not clear, though Pliny the Elder (Natural History, 7.57) relates that the games are very early, possibly older than the Olympic Games which were founded, according to tradition, in 776 B.C. Thus, the miniature cauldron votives from the Sanctuary of Zeus at Mt. Lykaion might have represented these prizes and, at the same time, symbolized an important aspect of the Greek thysia or sacrificial ritual—the consumption by human participants of the portions of the sheep or goats not given to the Olympian god in the burnt sacrifice. Such large cauldrons would have been used to hold the beverage for the shared community feast following the sacrifice.

Figure 11: Excavation of the Ash Altar of the Sanctuary of Zeus at Mt. Lykaion. 2007. Photograph courtesy of the Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project and David Gilman Romano, University of Arizona.

Figure 12a: Miniature tripod cauldron from the Sanctuary of Zeus, Mt. Lykaion. MTL 178. Photograph courtesy of the Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project and David Gilman Romano, University of Arizona.

Figure 12b: Miniature tripod cauldron from the Sanctuary of Zeus, Mt. Lykaion. MTL 178. Photograph courtesy of the Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project and David Gilman Romano, University of Arizona. Drawing by Christina Kolb.

Figure 13: Glencairn siren cauldron attachment, artificially colorized with photo editing software. Before the bronze cauldron aged to its current dark-green patina it would have gleamed like gold.

Conclusion

Of the some 80 known examples of siren cauldron attachments in the broader Near Eastern and Mediterranean worlds, the Glencairn siren attachment is, along with those from Toprakkale and Gordion, among the earliest known in the series. Rev. Pryke immediately saw the wisdom of encouraging further research on this artifact, including allowing sampling of it for metallurgical analysis. The publication of that analysis has contributed significantly to the scholarly discussion about the origins of siren cauldron attachments and adds more evidence that the early group of so-called “Oriental” or Near Eastern siren attachments of the 8th century B.C. were probably manufactured in the same locale. Whatever the source, the natural metal ore produced finished products that flashed like gold, adding to the allure of the cauldrons and their sirens who, like their Homeric namesakes, were meant to strike awe and terror in those who came too close (Figure 13).

Irene Bald Romano, Ph.D.

Professor of Art History, School of Art

Professor of Anthropology, School of Anthropology

Curator of Mediterranean Archaeology, Arizona State Museum

University of Arizona

David Gilman Romano, Ph.D.

Nicholas and Athena Karabots Professor of Greek Archaeology

School of Anthropology

University of Arizona

Endnotes

1 David Gilman Romano and Irene Bald Romano, Catalogue of the Classical Collections of the Glencairn Museum (Bryn Athyn, 1999), 46-48, no. 37.

2 D. G. Romano and V. C. Pigott, “A Bronze Siren Cauldron Attachment from Bryn Athyn,” MASCA Journal 2 (1983), 124-129.

3 Nassos Papalexandrou, “Are there Hybrid Visual Cultures? Reflections on the Orientalizing Phenomena in the Mediterranean of the Early First Millennium BCE,” Ars Orientalis 38 (2010), 31-48; Nassos Papalexandrou, Monsters, Fear, and the Uncanny in Early Greek Visual Culture (Austin, forthcoming).

4 Istanbul Archaeological Museum, acc. no. 41; M. N. van Loon,Urartian Art: Its distinctive trait in the light of new excavations(Istanbul, 1966), 107-110; H. V. Hermann, “Die Kessel der orientalisierenden Zeit,” Olympische Forschungen VI (Berlin, 1966), 74-76: Werkstatt A, no. 4.

5 Rodney S. Young, “The Gordion Tomb,” Expedition 1,1 (1958), 3-13, 11 for images of attachments; Rodney S. Young, Gordion Excavations Reports, Vol. I: Three Great Early Tumuli (Philadelphia, 1981), 104-110, nos. MM 2 and MM 3; 108, n. 34 for extensive bibliography on siren and demon cauldron attachments.

6 For stories of King Midas see A. Amrhein, P. Kim, L. Stephens, and J. Hickman, “The Myth of Midas’ Golden Touch,” Expedition 57, 3 (2015), 53-56.

7 Young 1958, 9.

8 E.g., Young 1981, 102, 108-9, 271-2.

9 C. Brian Rose and Gareth Darbyshire, eds., The New Chronology of Iron Age Gordion (Philadelphia, 2012), 15-16, 24-26, 75, n. 4.24; Richard Liebhart and Lucas Stephens, “Tumulus MM: Fit for a King,”Expedition 57, 3 (2015), 31-41.

10 P. E. McGovern, D.L. Glusker, R.A. Moreau, A. Nuñez, C. Beck, E. Simpson, E. Butrym, L. Exner, and E. Stout, “A Funerary Feast Fit for King Midas,” Nature 402 (1999), 863–864; Patrick E. McGovern, “The Funerary Banquet of ‘King Midas’,” Expedition 42, 1 (2000), 21-29.

11 Romano and Pigott 1983; see also A. Steinberg, “Appendix C: Analyses of Selected Gordion Bronzes,” in R. S. Young 1981, 286-289.

12 Young 1958, 10; Oscar White Muscarella, “The Oriental Origin of Siren Cauldron Attachments,” Hesperia 31, 4 (1962), 325; Young 1981, 110.

13 David G. Romano and Mary E. Voyatzis, “Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project, Part 1: The Upper Sanctuary,” Hesperia 83 (2014), 569-652 for the Ash Altar; 618-620 for the miniature tripod cauldrons. The Mount Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project is a project of the University of Arizona, in collaboration with the Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Tripolis, Arcadia, under the direction of David Gilman Romano, Mary E. Voyatzis, and Anna Karapanagiotou. See http://lykaionexcavation.org.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.