Glencairn Museum News | Number 6, 2013

Detail of a mosaic dragon from Glencairn's Great Hall archway.

Figure 1: Mosaic medallion on the wall of the first floor entryway area.

It was in the late 1920s, shortly before construction began on Glencairn, that the Bryn Athyn glassworks began work on a formula for mosaic glass. Previously the glass factory, part of Raymond Pitcairn’s Bryn Athyn Studios, had succeeded in recapturing the art of making pot-metal stained glass for Bryn Athyn Cathedral. Stained glass from the factory was also used to great advantage in Glencairn, the home Pitcairn built for his family and art collection. In addition to his admiration for medieval stained glass, Pitcairn was fascinated with the mosaics of Italy—especially those in the 5th and 6th century churches of Ravenna—and wanted to decorate his home with mosaics of a similar quality. He admired the matte finish of the Ravenna examples, which he regarded as superior to the high gloss finish found in modern mosaics.

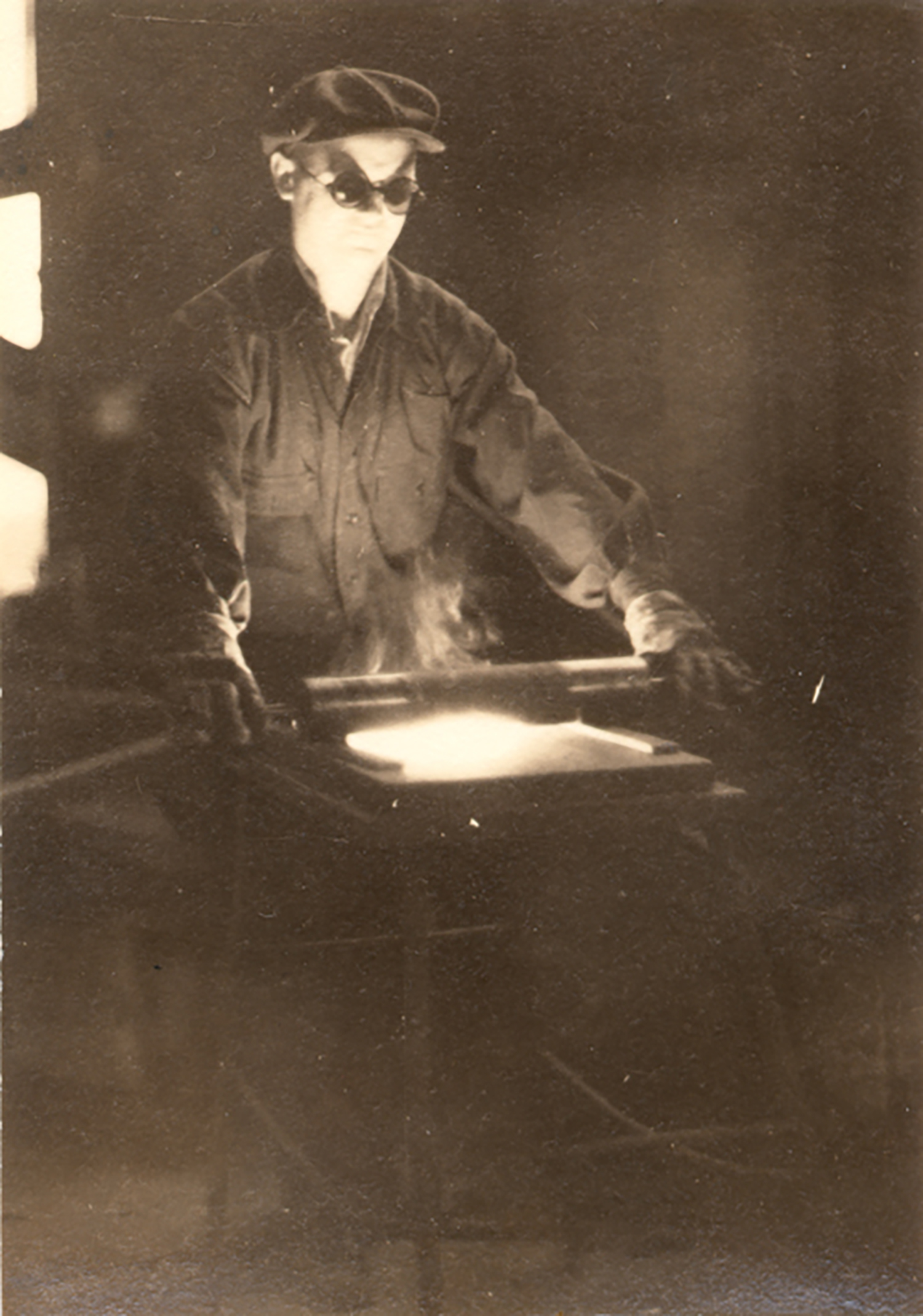

Figure 2: Ariel Gunther rolling out mosaic glass on a marver.

Pitcairn hired Ariel Gunther (Figure 2), a young member of the Bryn Athyn New Church congregation, to work in the glass factory. He quickly rose to become manager of the entire operation. In 1927 the six-week illness of David Smith, the principal glass blower, shut down glass production. Gunther used the opportunity to experiment with formulas for making mosaic glass, unexpectedly finding help in an old German manuscript. According to Gunther, “within two weeks I had perfected a workable formula and had begun to work on the many shades of color necessary to make the pictures and designs for wall and ceiling decoration” (Ariel Gunther, Opportunity, Challenge and Privilege, 1973, p. 101).

Figure 3: Mosaic glass is poured over gold leaf on a glass sheet.

Pitcairn was thrilled with the final results, writing several years later, “the glass for the mosaic we are producing in our own studios. It breaks with a non-glossy surface and is, I believe, the finest material which has been produced for mosaic in modern times” (Raymond Pitcairn to A. Cimarosti, November 10, 1931). Eventually Gunther also developed a way to make the distinctive gold tesserae (i.e. individual pieces of mosaic) found in Glencairn’s mosaics. For these tesserae a sheet of gold leaf was painstakingly sandwiched between a very thin layer of clear glass on top and a thicker piece of mosaic (about 3/8”) glass on the underside (Figure 3).

Figure 4: Albert Cullen setting tesserae for a mosaic design.

While Gunther worked in Bryn Athyn to develop formulas for mosaic glass, Albert Cullen (Figure 4), an artist from Canterbury, England, was hired by Pitcairn to study medieval mosaics in Italy. The principal sites he visited were Venice, Ravenna, and Rome. Cullen produced and sent to Bryn Athyn paintings and drawings to be used as inspiration and as teaching tools, and carefully recorded his observations in letters. One of his paintings of an Italian mosaic has been permanently preserved behind glass and inset into the left wall beside the Great Hall fireplace. Cullen, a careful observer, also considered the physics of how to set mosaic tesserae so that the light reflects properly for the viewer. As a result, the tesserae on Glencairn’s sloping chapel ceiling are set at an angle—a technique that Cullen recorded in a sketch while in Europe and sent back to Pitcairn. In 1928 Albert Cullen moved to Bryn Athyn to work for Pitcairn full time.

Many individuals worked together to produce the mosaics decorating Glencairn. The principal designers were Winfred S. Hyatt and Robert Glenn. The glass factory produced mosaic tesserae in many different shades. Slabs of mosaic glass, rolled out onto a marver, had to be cut by hand into the small pieces. The installation of the mosaics, on both walls and ceilings, was a complex, multi-step process.

Figure 5: Various types of mosaic birds decorate the Bird Room ceiling and a white mosaic peacock provides a backdrop for an ancient Egyptian libation bowl.

In Glencairn both the first floor and the fifth-floor chapel contain large-scale mosaics. The walls of the first-floor entryway are covered in mosaic designs (Figure 1) with symbols representing church, country, family and education—a theme that continues up the stairway to the second floor. Beyond the entryway, the Bird Room features mosaic birds on the partitioned ceiling and a large mosaic of a white peacock on the wall (Figure 5). The peacock mosaic is set into a recessed arch, providing an unusual backdrop for an ancient Egyptian libation bowl.

Figure 6: The Great Hall archway is decorated with a mosaic version of the Academy of the New Church seal.

The Great Hall contains the largest mosaic in the building: a rendering of the school seal for the Academy of the New Church (Figure 6), the alma mater of both Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn. The mosaic covers a large archway leading from the Great Hall to the Upper Hall. The design continues above the archway to the walls surrounding a third-floor balcony, surmounted by a mosaic of a recumbent lion. Two large ceiling trusses are covered with mosaic designs inspired by the Book of Kells.

Figure 7: The chapel ceiling on the fifth floor has mosaic designs from the Book of Revelation.

The Pitcairn family chapel has a magnificent mosaic ceiling (Figure 7), featuring a brilliant gold sun and four doves in the center panel. The angled sides depict the four beasts of the Apocalypse around the throne of God in heaven: “And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast was like a calf, and the third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle” (Book of Revelation 4:7).

(CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.