Glencairn Museum News | Number 1, 2026

The Museum’s refreshed Greek gallery features new objects on exhibit, engaging visuals that provide context, and new interpretive information, including details about provenance.

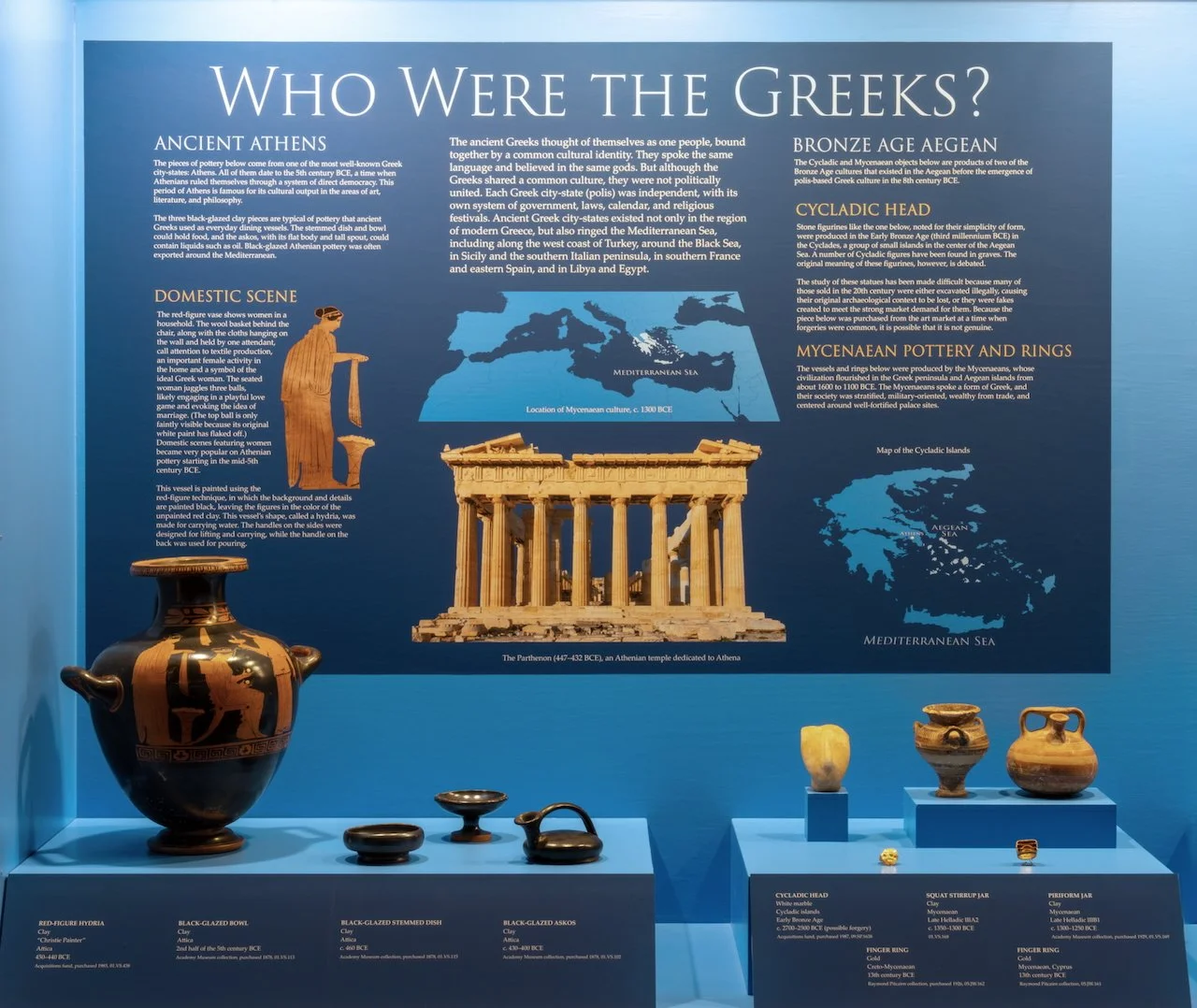

Come for a visit! Glencairn’s Greek gallery has a whole new look (Figures 1a–b).

Figures 1a–b: The Museum’s refreshed Greek gallery is now open to the public.

The Greek gallery first opened 30 years ago, in December 1996 (Figure 2). At that time, the gallery’s design heralded a new approach to exhibitions at Glencairn. As the “Director’s Notes” in the August 1997 Glencairn Museum Newsletter put it: “This is the first exhibition [at Glencairn] to begin with the premise that the Museum’s mission is to teach about the history of world religion by means of art and artifacts. Thus, the display is thematic rather than chronological….”

Figure 2: The Greek gallery with its 1996 design.

The earlier gallery, unveiled at the opening of Glencairn Museum to the public in January 1982, had included both Greek and Roman pieces in a new display organized by object type and time period (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Greek and Roman gallery during the opening of Glencairn Museum in 1982.

Figure 4: The gallery refresh team: Glenn Greer, Bret Bostock, Ed Gyllenhaal, Wendy Closterman, and Edwin Herder. (Missing: Marie Daum and Kirsten Gyllenhaal).

While maintaining the same basic thematic arrangement, the gallery has now been refreshed in three ways: new objects on exhibit for the first time in decades; new visuals and graphics; and new information in the labels. (See Figure 4 for the gallery refresh team.)

New Objects

Eleven pieces that have remained in storage for decades are newly on view in the gallery, while a small number have returned to storage. Because the Museum’s Greek and Roman collection is larger than can be meaningfully displayed at one time, rotating objects allows visitors to engage with different parts of the collection, offering fresh opportunities for appreciation and reflection.

For example, three 5th-century BCE Athenian black-glazed dining vessels accompany the Museum’s Athenian red-figured hydria from the same century (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Three 5th-century BCE Athenian black-glazed dining vessels are newly on exhibit.

A third veiled female head from Cyprus joins the two heads previously on exhibit. Heads like these were often set up in Cypriot sanctuaries as dedications (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The piece in the center has joined the other Hellenistic Cypriot heads on exhibit.

A small figure of an animal, perhaps a pig, is now nestled among the small statues and vases that the ancient Greeks typically offered as religious dedications (Figure 7). Ancient visitors to sanctuaries left behind objects like these as gifts for the gods, accompanied by a prayer asking the gods for a favor or expressing thanks.

Figure 7: Animal votive from Cyprus.

In the Daily Life exhibit, visitors can look for a bronze bracelet that joins the earrings, pin, ring, and necklace on the jewelry board alongside several pieces of painted pottery from different regions in the ancient Greek world (including Figures 8–10).

Figure 8: Athenian kylix band cup, 3rd quarter of the 6th century BCE.

Figure 9: Boeotian skyphos, end of the 6th to the beginning of the 5th century BCE.

Figure 10: Apulian pyxis lid, late 4th century BCE.

New Visuals

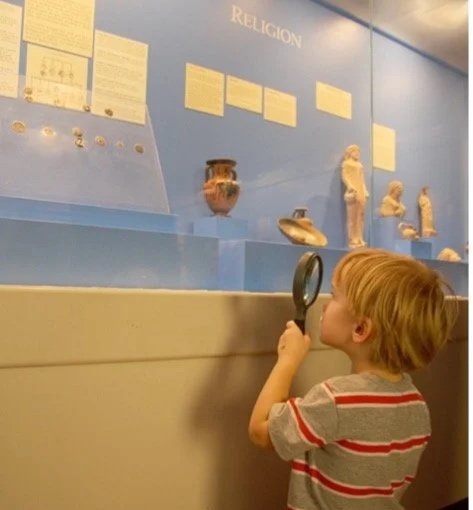

Returning visitors will immediately notice the difference when they enter the gallery. Engaging graphics that combine text and images draw in viewers with their dynamism. The graphics are designed to complement the ancient objects and spark the imagination by adding visual context. For example, stone and terracotta religious dedications now stand in front of a photo of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, evoking a sanctuary context where ancient Greek worshippers gave objects like these to the gods (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Statues typical of religious dedications appear in front of an image of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi.

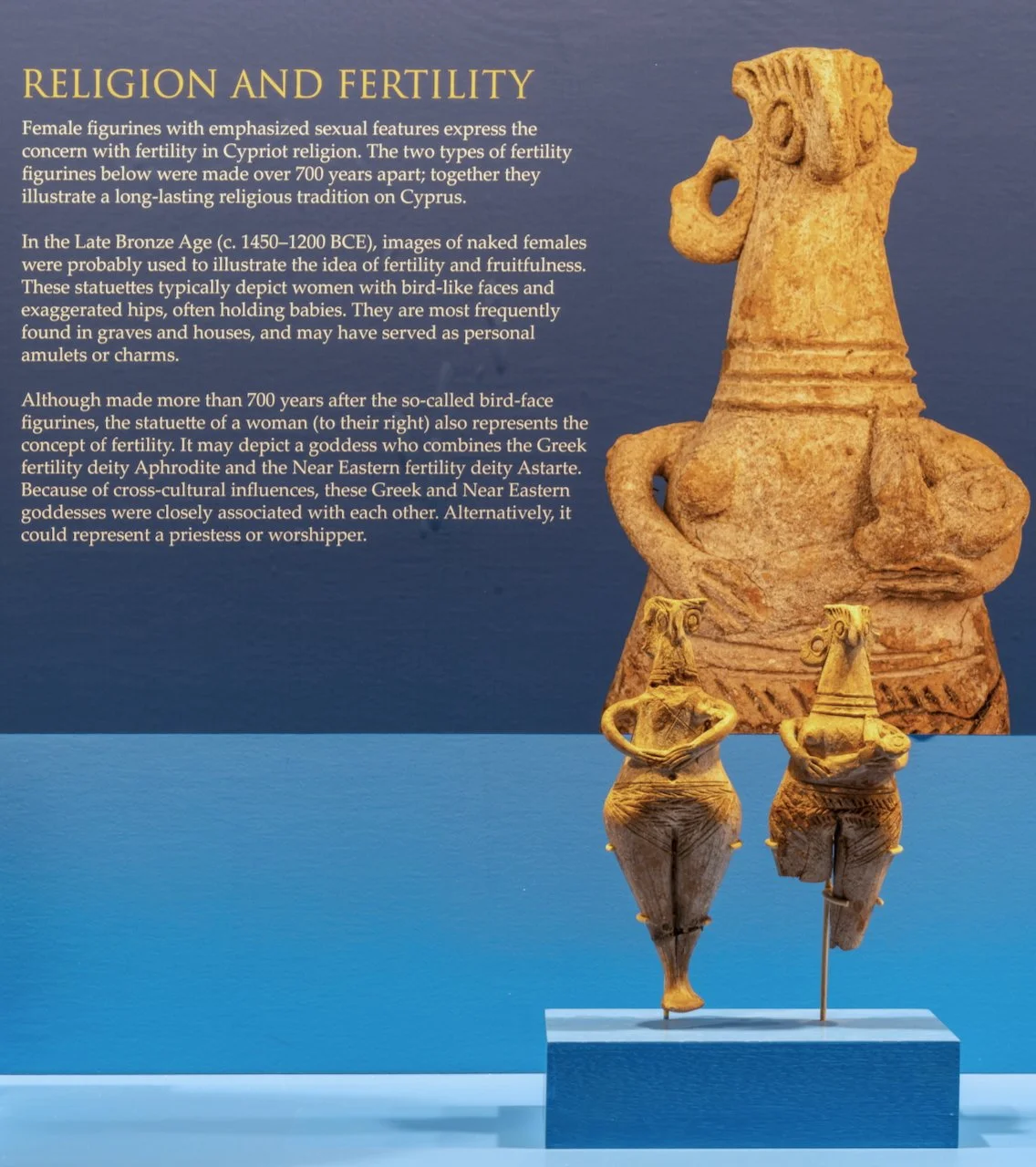

Other visuals help visitors to notice details on the Museum’s objects. A close-up photograph of the Late Bronze Age Cypriot bird-faced figurine, for example, makes it easier to pick out the baby in the original object (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Late Bronze Age Cypriot bird-faced figurines.

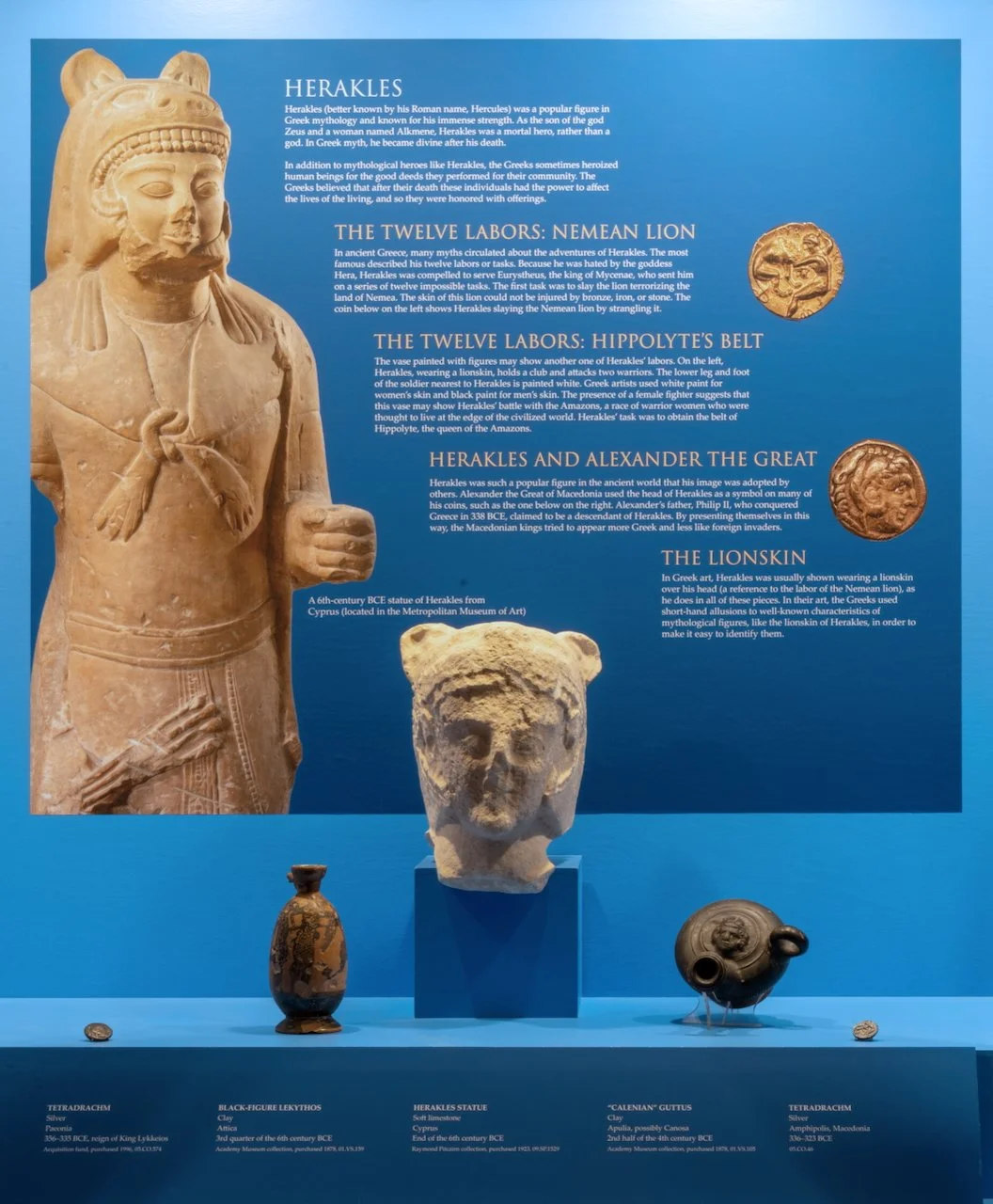

Comparing the Museum’s head of the hero Herakles with a photograph of a Herakles statue in the Metropolitan Museum of Art makes the weathered remains of Herakles’ lionskin hood on Glencairn’s statue more visually understandable (Figure 13). Alluding to the myth of Herakles slaying the Nemean lion, Greek artists typically portrayed Herakles as wearing a lionskin, making his identity instantly recognizable.

Figure 13: Cypriot stone head of Herakles wearing a lionskin.

The ability to create these large graphics in-house has made a gallery refresh of this type more affordable and feasible than in the past. The renewal of the Greek gallery is the first of a number planned during the next several years.

New Information

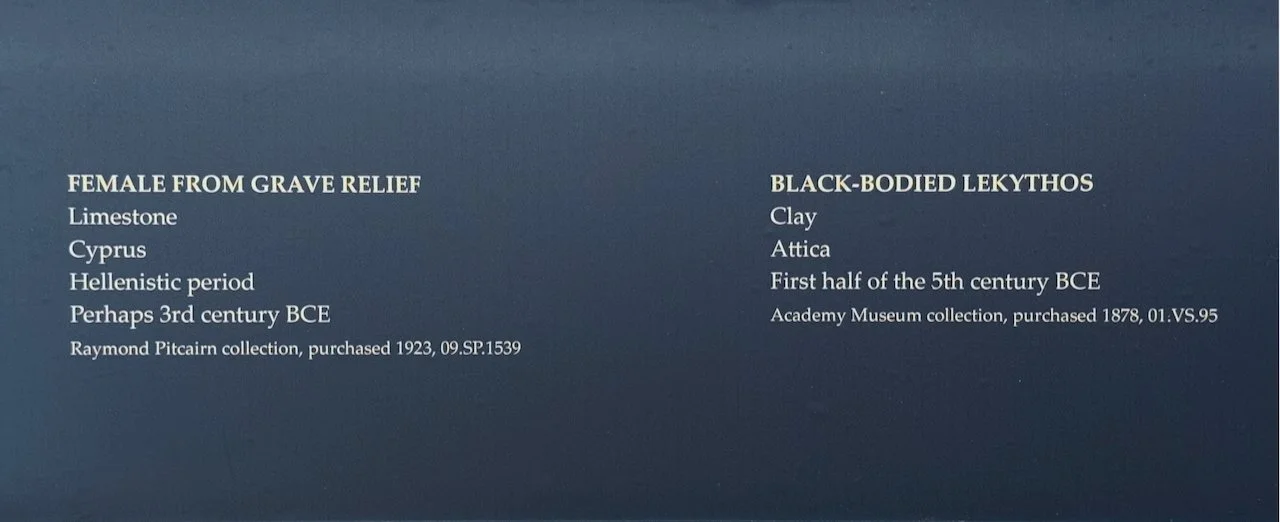

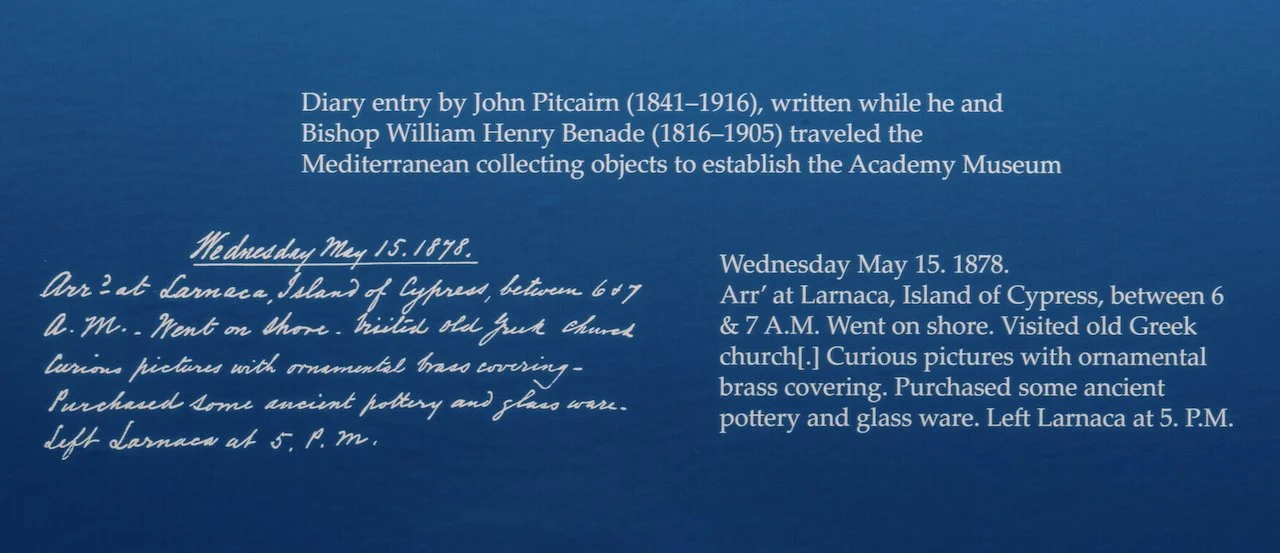

Visitors will also find something new on Glencairn’s object labels: information about how the objects on display came to Glencairn Museum (Figure 14). Glencairn itself, the castle-like home built by Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn between 1928 and 1939, was given, along with the Pitcairns’ significant art collection, to the Academy of the New Church schools in 1980. At that time the Academy already had a long-established museum, founded in 1878 when John Pitcairn (Raymond’s father) and Bishop William Henry Benade began acquiring pieces for it (Figure 15). When Glencairn Museum opened to the public in 1982, these two collections were brought together. The object labels in the Greek gallery now identify, when known, which pieces came from the Raymond Pitcairn collection, which belonged to the Academy Museum, and which were later purchased or received as gifts. These details begin to introduce visitors to the provenance of each object as well as the layered history of the Museum’s collections.

Figure 14: Examples of object labels that identify a piece that was originally in the Raymond Pitcairn collection and an object that came from the Academy Museum collection, including the dates of purchase.

Figure 15: An excerpt from John Pitcairn’s diary reproduced in the gallery’s new graphic labels.

We invite you to come experience the newly refreshed Greek gallery for yourself, whether touring Glencairn for the first time or returning to revisit some old favorites and enjoy new pieces. The Greek gallery is currently included in the Highlights tour, the Sacred Adornment tour, and the Family Backpack tour. You can also explore the Greek gallery and the whole building at your own pace during Third Thursdays starting in April 2026 and during the Sacred Arts Festival. Check Glencairn’s website for details!

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.