Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2022

You taught two classes at Bryn Athyn College this academic year that made substantial use of Glencairn Museum. In general, how did these classes involve Glencairn in ways that were different from a regular field trip?

No matter the educational level, field trips to museums are always a highlight, and I try to schedule them in my college classes whenever I can.

In 2021–2022, I taught two classes—Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums and Women in Classical Antiquity—that integrated Glencairn Museum into the course design in ways that went beyond the usual field trip visit. Glencairn provides so many fantastic opportunities for transformative hands-on and active learning. My classes received a rich array of opportunities to apply what they were learning. In addition to benefiting from what Glencairn has to offer, in each course the students were given an assignment in which they were asked to draw on what they had learned in the course in order to give something of value back to Glencairn.

Figure 1: Nine sheep, labeled with the names of Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn’s children, are carved above the entrance to Glencairn.

What are some of the ways that students were able to apply what they were learning at Glencairn?

Inspired by Henry David Thoreau’s observation “The question is not what you look at, but what you see,” the main goal I have for the course Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums is that at the end of the term students view the world around them differently—that they look at objects, buildings, and the landscape around them with fresh eyes, seeing how they are rich with meaning. What better place to learn to look carefully and see new things than the intricate, beautiful, and inspiring building of Glencairn!

Students not only attend Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums in Glencairn’s classroom, but they also participate in a hands-on experience every day that invites them to apply and explore a major concept from the class. Many of these experiences involve Glencairn’s historic building and grounds as well as the Museum exhibits and collections. The students also interact with members of Glencairn’s staff as a part of several of these experiences, learning first hand about how museums work. In addition to involvement in Glencairn, this year we also took trips to other nearby locales: Cairnwood Estate (also in the Bryn Athyn Historic District), the Bryn Athyn cemetery, a property in the Bryn Athyn borough with the remains of a Colonial-era mill, and Fonthill, the home of Henry Chapman Mercer in Doylestown.

Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums consists of three main units. The first introduces the rationale and methods of material culture studies. Two fundamental principles are 1) starting with careful and multi-sensory observation of details, and 2) comparing the object under consideration with other objects selected based on the research question. One early observation exercise asks the class to try to remember what the front entrance of Glencairn looks like, an entrance that the students have recently walked through to get to the classroom. Collectively, the students brainstorm what they remember, and then we walk outside and really look. While students usually remember some elements of the entrance, classes are also struck by what they never really noticed before. Often, classes are surprised by the delightful sheep arching above the door, labeled with the names of Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn’s children, or by the way the glass in the door is arranged to resemble an expansive tree (Figure 1). This experience at the beginning of the course brings home Thoreau’s point that we can so easily look at things in our day-to-day lives and not really see them.

Figure 2: Bryn Athyn College students in the Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums course view Glencairn’s Great Hall from the third-floor balcony.

The second unit explores different ways museums and historic houses communicate with the objects in their exhibits. As part of this unit, the class visited a number of Glencairn’s galleries to analyze exhibit strategies and visitor experiences. Drawing on various exhibition categories typically outlined in museum studies textbooks as well as on information about different visitor types as defined by John Falk, an expert in museum learning, the students identified organizing principles in the galleries and considered the atmosphere created by the use of color, layout, and other visual cues. For example, the way objects are used in Glencairn’s Great Hall (Figure 2), a contemplative space where medieval pieces were built into the building itself and are displayed as they were originally set up by Raymond Pitcairn, differs from galleries like that of ancient Egypt (Figure 3), where objects are arranged chronologically and topically around themes like the Egyptian pantheon or mummification, and learning is supported by dioramas about mummification practices and ancient Egyptian beliefs relating to the afterlife.

Figure 3: Glencairn’s ancient Egyptian gallery.

Members of the Glencairn staff led one exploration that was focused particularly on different ways that exhibits manifest the Museum’s mission, with its focus on inviting visitors to consider the shared human desire to seek meaning and purpose through the exploration of diverse religious belief and practice. How can an exhibit of objects, which are tangible manifestations of religion, also point to or invite consideration of inner human experiences?

The last unit focuses on archaeology, introducing students to foundational concepts and exploring topics in archaeological and museum ethics. This section of the course begins with a consideration of how places that once were sites of bustling human activity become archaeological sites over time. This process is not arcane or obscure, but it happens around us all the time through a combination of natural effects, such as weather moving soil, and human effects, such as the movement of human activity away from a particular location. After working with textbook materials about the formation of archaeological sites, the class visits an out-of-the-way place near Glencairn to see the principles of archaeological site formation in action. The students enjoy exploring this place, observing site formation processes, and trying to reconstruct what the location originally looked like. Spoiler alert—when the Pitcairns lived at Glencairn, this was a tennis court (Figure 4)!

Figure 4: A former tennis court used by the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn family when they lived at Glencairn.

In sum, the curriculum of Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums draws on elements of place-based education. Place-based education seeks to link learning to local places and to the communities where students are doing the learning. Its goals include grounding and vivifying abstract ideas through concrete application to the surrounding environment and fostering a sense of connection to the local community. Glencairn—both the building and its collections—is the focal point of the course, serving as a kind of lab for exploring and applying course concepts. The opportunities that the Museum provides to enrich student learning experiences tremendously, and students end the course feeling a deep and warm connection to Glencairn.

In what ways did the classes aim to give something back to Glencairn Museum?

In both Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums and Women in Classical Antiquity, students are asked to apply what they have learned to produce something useful for the Glencairn Museum staff. Real world application of what students are learning, with the goal of helping others, can deepen student learning and imbue it with greater meaning.

Figure 5: Students in the Women in Classical Antiquity course pose in Glencairn’s Roman gallery.

The final project in Women in Classical Antiquity asks students to draw connections between an object in the Museum’s Greek or Roman galleries and what they have been learning that term about the lives, ideology, and experiences of women in ancient Greece and Rome (Figures 5-7). The outcome is not only a paper, but also a formal presentation that the students give in the gallery to members of the Glencairn Museum staff as well as to classmates. I emphasize to the students that, while the staff knows the objects very well, the students know a lot about women in the ancient world and can make a genuine and useful contribution by sharing this historical and social context.

Figure 6: A student presents about women’s rituals in the worship of the god Dionysos in Glencairn’s Greek gallery.

Figure 7: A student presents about rituals for girls and women in the worship of the goddess Artemis in Glencairn’s Greek gallery.

Several topics the students selected this year relate to women’s involvement in ancient religious practices, such as women’s rituals in the worship of the goddess Artemis or the god Dionysos, presented respectively in connection with a terracotta figurine of Artemis and a vase showing maenads, mythical female followers of Dionysos. Other examples include women’s roles as makers of votive offerings or as priestesses, presented in relation to examples of terracotta offerings and a vase showing a woman leading a bull to sacrifice. Other presentations explored other social contexts, such as ancient concepts of beauty in relation to a pot used for cosmetics, or how ideology about women informed ancient gynecology in relation to a Roman medical kit.

I am grateful to the Glencairn Museum staff who attended these presentations. They provided positive feedback about the experience and one staff member noted that it got them brainstorming ways they might incorporate ideas from the presentations into programming.

Figure 8: Students in the Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums course examine the decoration on the large bronze door leading from Glencairn’s Cloister to the Great Hall.

For the final project in Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums, students are asked to apply what they have learned to a pre-existing, on-going project for Glencairn. This year the class worked on furthering a study documenting art that was commissioned by Raymond Pitcairn specifically as part of the decoration of Glencairn. This study was initially started several years ago by a student intern, and a previous Artifacts, Archaeology, and Museums class contributed to it a few years ago. As part of the assignment, the students collectively identify what additional information they want to add in order to contribute value to the resource. This year’s class decided to break into groups to pursue three main goals.

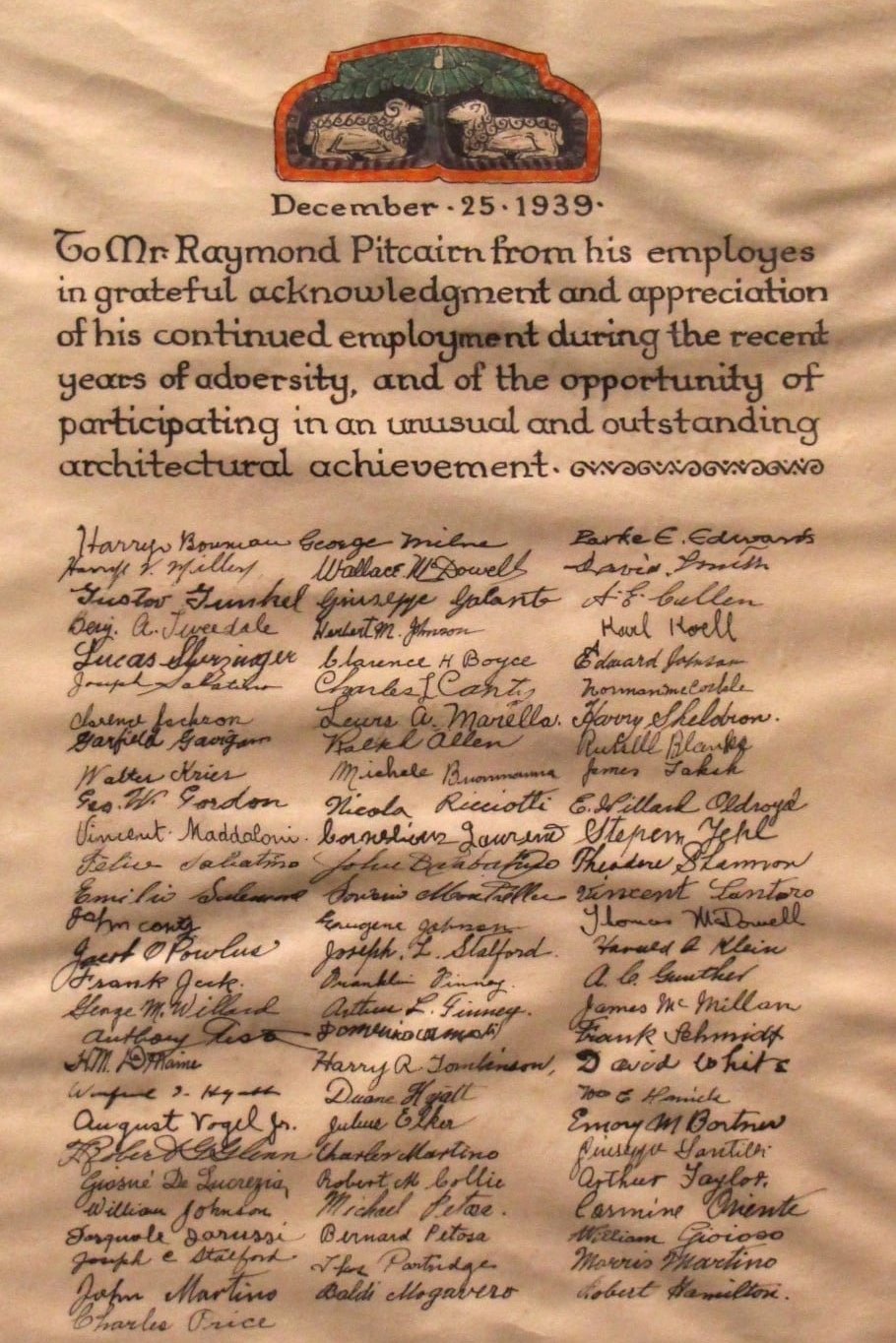

One group used available resources to add the names of artists who had worked on the building of Glencairn to the documentation, where known (Figure 10).

Figure 9: Students study the Christmas window in Glencairn’s fifth-floor Chapel.

Figure 10: This letter to Raymond Pitcairn, dated December 25, 1939, was signed by dozens of the workmen, craftsmen, artists, and others who helped build Glencairn.

Figure 11: Audubon bird figures decorate Glencairn's third-floor stairwell.

Another group focused on the representation of birds, which are pervasive in the art made for Glencairn, seeking to come up with a total count and to improve the identification of the different types of birds represented (Figure 11). A third group expanded a list of symbolic meanings, drawn from the theological writings of Emanuel Swedenborg, that inspired Raymond Pitcairn in his choice of some of the images in the art made for Glencairn.

In the class discussion about this experience at the end of the course, students reported that it was exciting and fulfilling to put what they had learned to use. They also noted that they gained a deeper appreciation for the amount of work and time involved in doing this sort of study. Individual students shared further insights. For example, one felt that they had learned more about what values and ideas inspired Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn. Another loved learning about the variety of pieces an individual artist had worked on. Lastly, some students who had had conversations with Glencairn Museum staff about what they were working on shared that they were inspired to find staff members excited and eager to see the results.

Do you have ideas for additional ways to incorporate Glencairn into your classes?

My students and I were quite taken with the Museum’s use of QR codes on some labels to provide interested visitors with more resources about objects and their context. One dream I have for the future is to develop my own and my students’ skills in the digital humanities, and then use those skills to produce some resources for the Museum.

Several of my colleagues at Bryn Athyn College also involve Glencairn in their classes in innovative ways. Dialoguing more with them and the Museum staff will certainly generate new ideas as well.

Glencairn has been a wonderful educational partner for many years. I am grateful to the staff for welcoming and supporting a more intensive use of the building and its collections, and for engaging with my students so generously. And I’m looking forward to new modes of educational collaboration that will emerge in the future.

(Interviewed by CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.