Glencairn Museum News | Number 9, 2019

This depiction of adulthood in Frank Jeck’s “Ages of Man” carving on Glencairn’s first-floor staircase seems to have been inspired by two woodcuts produced by the American artist Rockwell Kent titled, “Man” and “Woman.” The images were published in Kent’s 1920 book, Wilderness: A Journey of Quiet Adventure in Alaska.

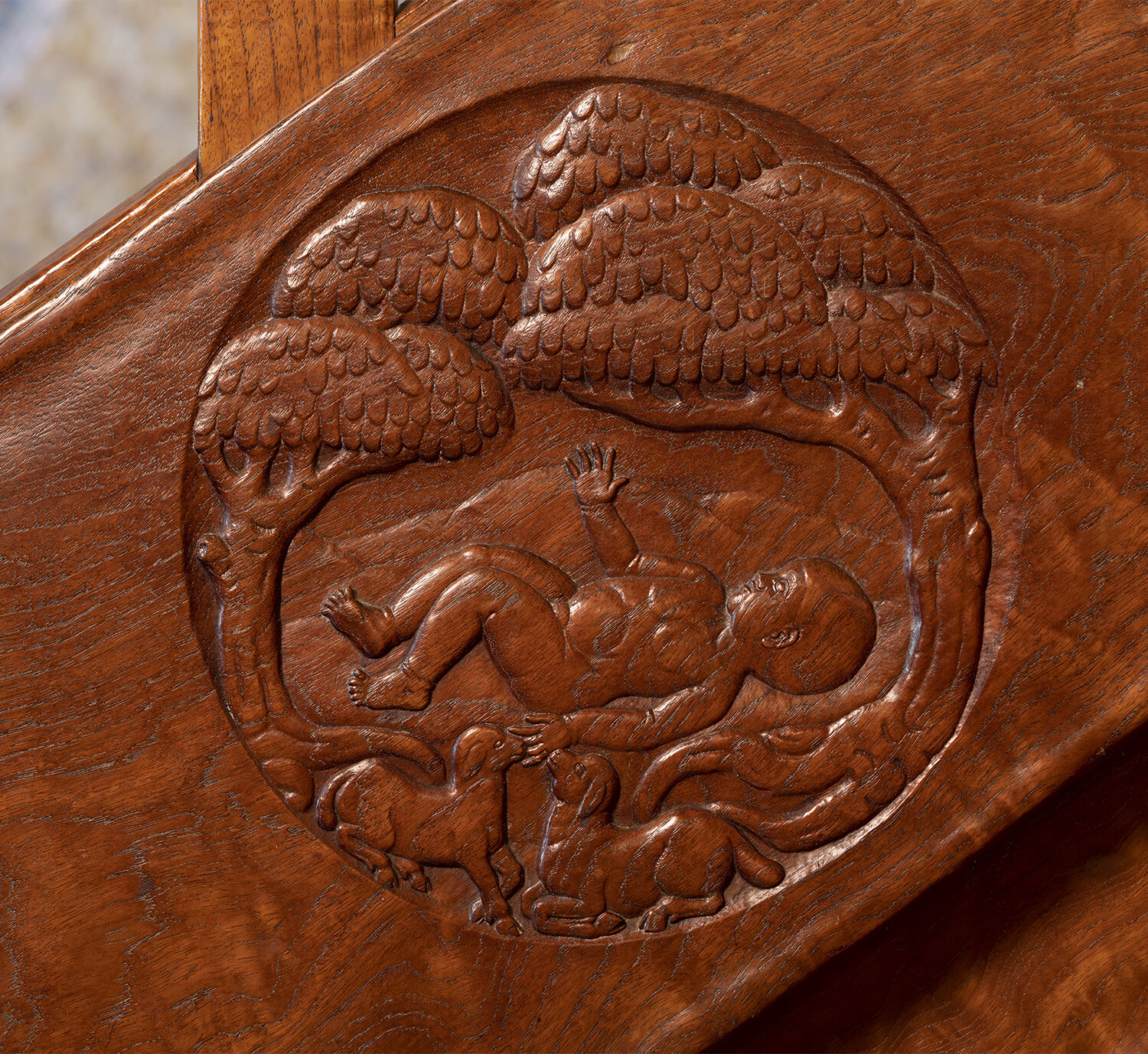

(Continued from Part One.) On Glencairn’s first floor staircase is a series of four large, teakwood medallions on the theme of the “Ages of Man,” carved by Frank Jeck. Ascending upward, they depict the stages of human development: infancy (a baby under leafy branches with lambs); childhood (children placing garlands on another child); adulthood (a couple with a baby); and old age (a husband reading to his wife).

Figure 1: Frank Jeck carved a series of four teakwood medallions on the theme of the “Ages of Man” on Glencairn’s first floor staircase.

No drawings or models have yet been found for these medallions in Glencairn’s archives or collections. However, it seems clear that the work of the American artist Rockwell Kent provided the inspiration for the two figures depicting adulthood (see Figures 2, 3, and 6). The style and poses of the man and woman in Jeck’s carving seem almost identical to two woodcuts by Kent titled “Man” and “Woman” from his 1920 book, Wilderness: A Journey of Quiet Adventure in Alaska. In the summer of 1918 Kent traveled to Alaska with his son, and Wilderness, an illustrated journal, was the result. It is not known whether Raymond Pitcairn introduced Frank Jeck to Kent’s “Man” and “Woman” woodcuts, or whether Jeck encountered them on his own and presented the idea to Pitcairn. (The full text of Kent’s journal, complete with illustrations, is available online here.)

Figure 2: “Woman,” a drawing from Rockwell Kent’s 1920 book, Wilderness: A Journey of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (p. 119).

Figure 3: “Man,” a drawing from Rockwell Kent’s 1920 book, Wilderness: A Journey of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (p. 115).

Parallels to designs for the other three Glencairn medallions, however, do not appear in Wilderness, or even in a 1933 book of Kent’s collected works owned by Raymond Pitcairn. (Pitcairn bought the 1933 book of Kent’s collected works around the year 1950, but it is possible that he also owned other books by Kent that have not survived in his library at Glencairn.) The inspiration for these three medallions is not known, and it may be that Jeck designed them himself.

Figure 4: “Infancy”

Figure 5: “Childhood”

Figure 6: “Adulthood”

Figure 7: “Old Age”

The idea for the “Ages of Man” theme of the Glencairn medallions may also have been inspired by Kent, who in 1918 published a portfolio of ink drawings titled, The Seven Ages of Man: Illustrated in Four Drawings. Kent’s drawings depicted four of the famous “seven ages” described by William Shakespeare in As You Like It:

“All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant…”

Inglenooks (built-in bench seats adjoining fireplaces) were popular during the Arts and Crafts period. The Great Hall fireplace at Glencairn provides the focal point for an inglenook with carved teakwood benches on either side. Frank Jeck carved rams and ewes on the armrests of both benches. Sheep are a recurring theme in Glencairn symbolizing family; the ram represents the father and the ewe is the mother.

Figure 8: Two benches carved by Frank Jeck illustrating the uniting of Raymond and Mildred’s families through marriage were made for the inglenook in Glencairn’s Great Hall.

Figure 9: A carved ram armrest on one of the inglenook benches.

Figure 10: A carved ewe armrest on one of the inglenook benches.

These two benches also illustrate the uniting of Raymond and Mildred’s families through marriage. Their names, and those of their families, are inscribed on the benches and arranged into a genealogy. Jeck carved the names of Mildred’s parents and siblings into the backrest of the right-hand bench, and the names of Raymond’s parents and siblings into the backrest of the left-hand bench. On the ends of the benches are carved the names of Raymond and Mildred’s children, and just above these names are the intricately carved names of their two homes in Bryn Athyn: “Glencairn” and “Cairnwood.”

Figure 11: The names of Raymond Pitcairn’s parents and siblings are carved into the backrest of the left-hand bench.

Figure 12: Above the names of Raymond and Mildred’s children are the intricately carved names (including inhabited initials) of the family’s two homes in Bryn Athyn: “Glencairn” and “Cairnwood.” (The two elements have been combined in this photograph for the sake of comparison.)

While it is not known exactly when Jeck stopped working for Pitcairn, it is likely that he left shortly after 1942, when the workshops in Bryn Athyn began to shut down and most of the craftsmen left for other jobs or to serve in the military. A letter sent to Pitcairn from Jeck’s brother Mathews in 1960 sadly reported that Frank had suffered a stroke two and a half years earlier and could no longer speak. Mathews was hopeful that a letter from Pitcairn would spark a reaction, because “he always thought a lot of you” (Mathews Jeck. Letter to Raymond Pitcairn. 1960). Pitcairn promptly wrote letters to both Mathews and Frank, telling Frank that “I often think of you when looking at the carving which you did for the Church [Bryn Athyn Cathedral], on the little bed which now belongs to my son Lachlan, and some of the things at Glencairn.”

Pitcairn once wrote that “the art of an age outlives all else of its civilization,” and that “the art of any epoch holds the spirit of the age.” The woodcarvings at Glencairn have now outlived both Frank Jeck and Raymond Pitcairn, but they stand as a lasting legacy to be enjoyed by future generations of art lovers who will visit the home of the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn family.

For other works by Frank Jeck, see Glencairn Museum News no. 3, 2018: “Glencairn’s ‘Tyldal Chair’: A Twentieth-Century Revival of Twelfth-Century Norwegian Woodcarving.”

This issue of Glencairn Museum News is part two of a two-part series. Click here to read Part One.

(KHG/CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.