Glencairn Museum News | Number 4, 2018

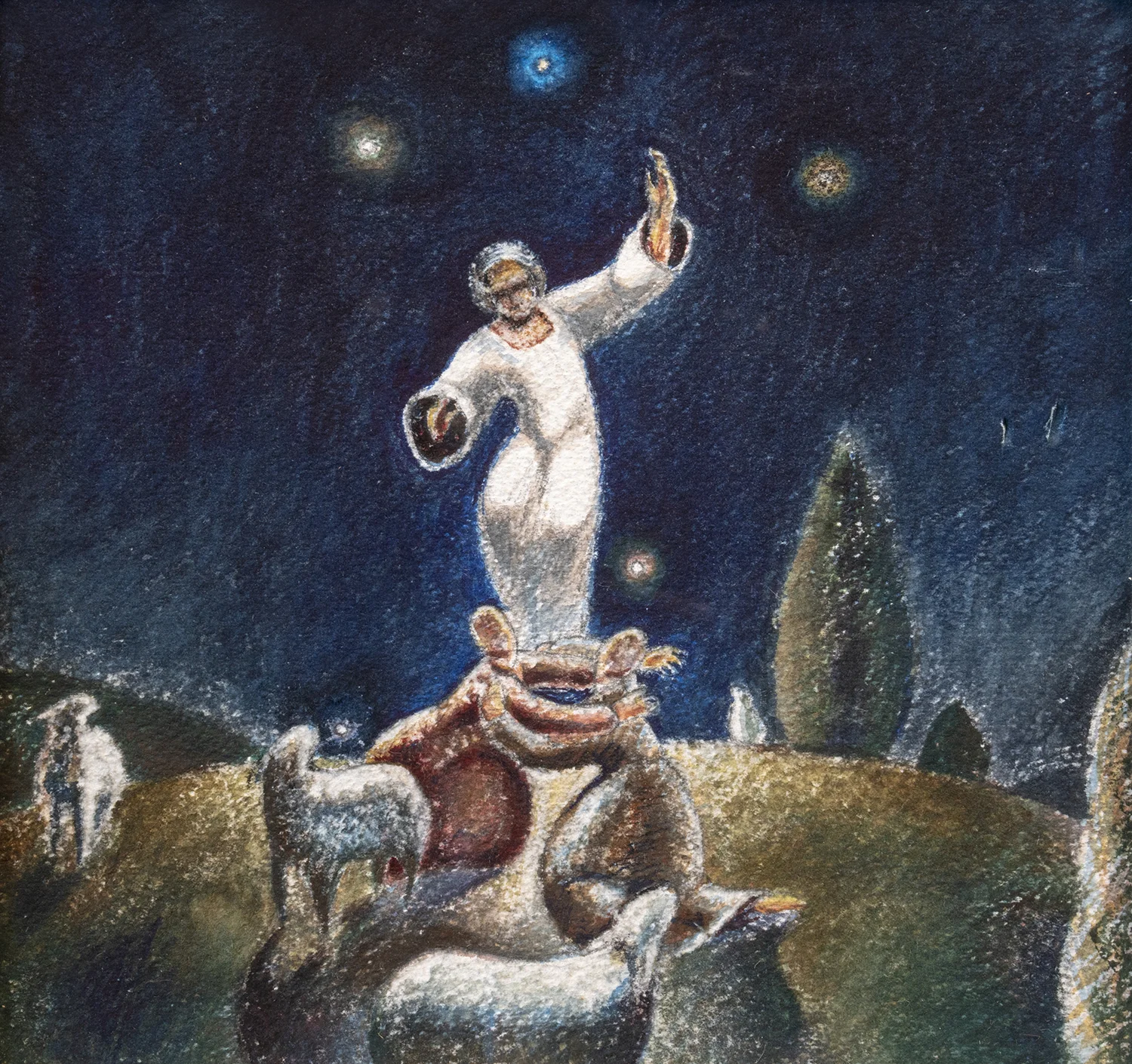

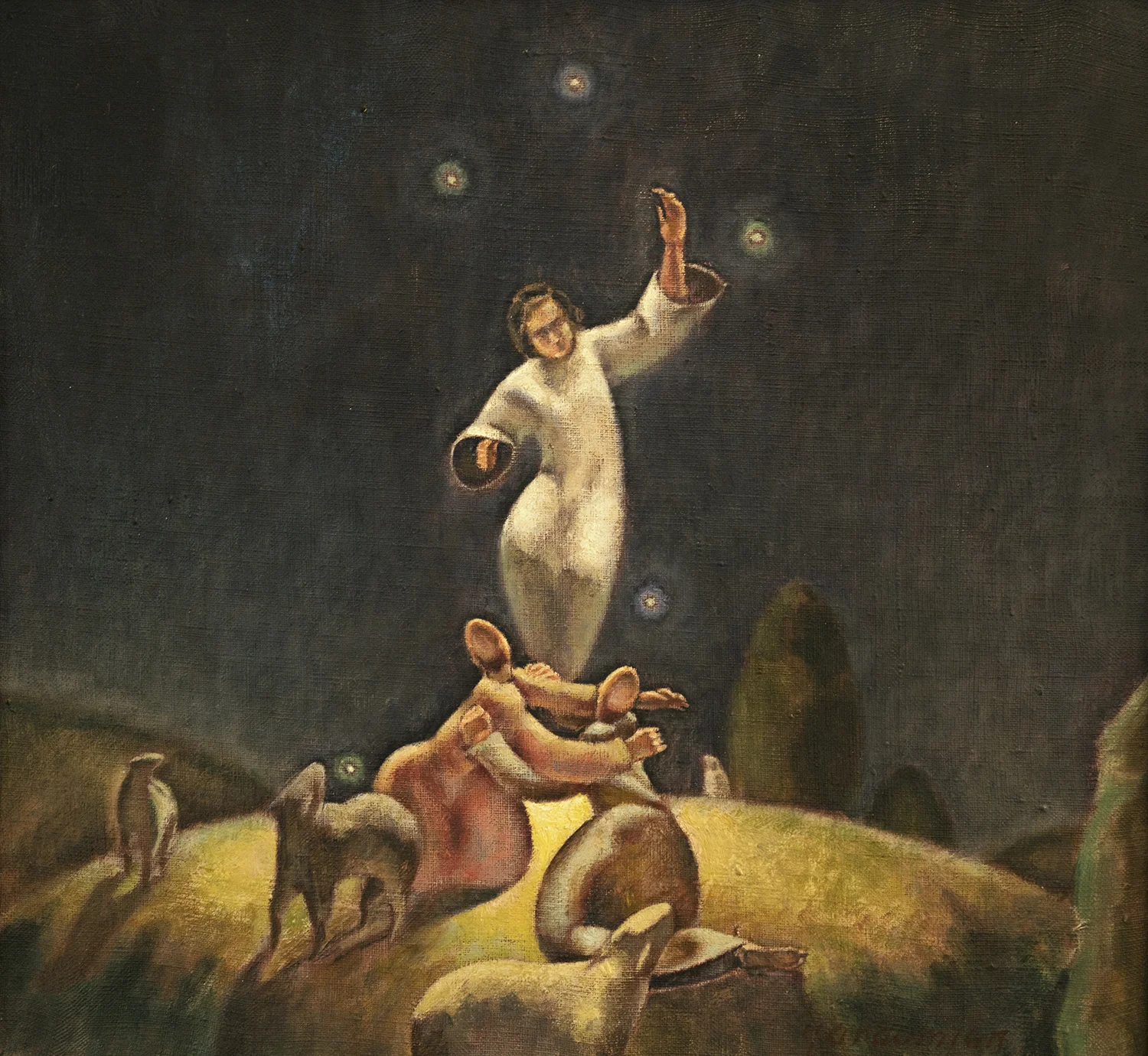

Annunciation to Shepherds. According to Nishan Yardumian, the artist, this painting represents “an idea born. The angel is an idea appearing, the shepherds are the trauma of change an idea might occasion in one’s life.”

Figure 1: Self Portrait. Oil, 1977. On loan from Siri Yardumian Hurst.

Nishan Richard Yardumian was one of 13 children born to Armenian-American classical music composer Richard Yardumian and his wife, Ruth Seckelman, members of The Lord’s New Church in Bryn Athyn. Yardumian taught painting in Bryn Athyn for many years, at both the Academy of the New Church Secondary Schools and Bryn Athyn College. He was an artist as well as a teacher, and was passionate about both professions. According to Yardumian, “Painting aims at the universal with the hopes that each individual can find his identification with it. Teaching aims at the individual with the hope of developing the universal.”

As a devoted reader of 18th-century Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg, Yardumian believed that religion was a central aspect of human experience. He maintained a special interest in religious art, believing that the artist must learn to discern the spiritual from the mundane in the world around him, and seek to communicate spiritual ideas to others through his paintings. He was fond of joking that his paintings were pieces of his mind, and he loved “giving people a piece of his mind.” “Ideally paintings,” according to Yardumian, “add to a room something spiritual, that is, something genuinely human. One may hang a painting and have thereafter on his wall a ‘window to the soul.’”

Figure 3: Annunciation to Shepherds. Luke 2:8-14. Oil on canvas, circa 1975. On loan from Siri Yardumian Hurst.

Siri Hurst, Nishan Yardumian’s widow, who owns many examples of her late husband’s work, says, “He loved to paint stories from the Bible because of what they mean in our lives. Although religious imagery wasn’t popular in the art world of his day [1970s and ’80s], his work found a receptive home at Glencairn Museum, whose mission supports an appreciation for our common spiritual history.”

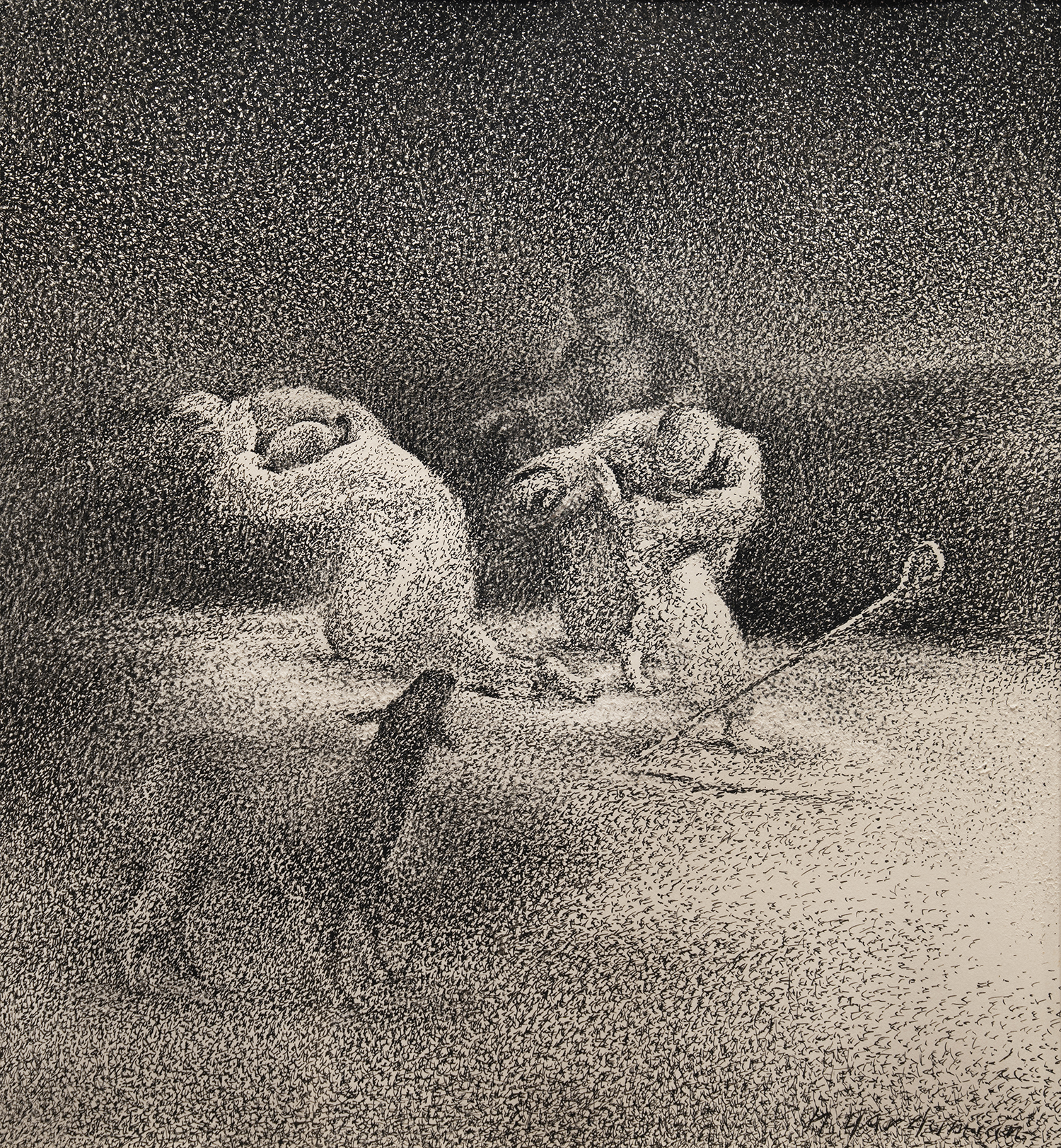

Figure 4: Noah Entering the Ark. Genesis 7:7. Oil, 1981. On loan from Siri Yardumian Hurst.

Figure 5: Annunciation to Mary. Luke 1:26-38. Pen and ink, 1979. On loan from Miriam Yardumian.

Figure 6: Supper at Emmaus. Luke 24:30-31. Oil on canvas, circa 1981. On loan from Kent Junge.

Dr. Martha Gyllenhaal, Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Bryn Athyn College and a close friend of Yardumian, was one of several speakers at the exhibition opening for A Window to the Soul. According to Gyllenhaal, “Nishan Yardumian believed that an art exhibit is essentially a discourse between the artist and the viewer—each person brings their best self to the process. With the opening of this exhibition we have an unprecedented opportunity to see what Yardumian himself never saw, a retrospective display of his biblical narratives, including both preliminary and finished works. This is an opportunity to trace the arc of his career from its burgeoning explorations to its final accomplishments, and thereby strike up a conversation with him.”

Figure 7: Baptism of Christ. Mark 1:9-11. Based on 12th c. French capital at Glencairn Museum. Tempera. On loan from Stephen Morley.

“The Christian art tradition that spoke the most directly to Yardumian was that of the 12th century or Romanesque period, particularly its sculpture, which shows vitality through the use of well-placed swirls or S-curves. Figures often look like they are dancing—the flick of a hem, the raising of a knee. And yet in Romanesque art the emotions are restrained. For example, in Yardumian’s drawing of a Glencairn Crucifixion capital (Figures 8 and 9) we do not see Christ’s agony, but rather the part of the story where Joseph of Aramathea is carefully taking Him down from the cross—the Deposition of Christ. The slumping together of their bodies shows tenderness and pathos.”

Figure 8: Descent from the Cross. Limestone capital, 12th c. (?) Spain. 09.SP.53. See Figure 9.

Figure 9: Descent from the Cross. John 19:38-42. Pen and ink, 1977. Collection of Glencairn Museum, donated by Vera P. Glenn. Based on 12th c. (?) limestone capital from Spain in the collection of Glencairn Museum. See Figure 8.

“Likewise, Yardumian’s study of a Crucifixion in the Louvre (Figure 10; Louvre RF 1082), which would have been part of a large, freestanding ensemble of figures from the Deposition, shows no blood or horror—instead a deep calm, the fulfillment of prophecy. He also painted several original studies depicting other more dramatic portions of the Crucifixion story, but they were commissioned for a special purpose—to be projected on a screen during an Easter tableaux (Figures 11 and 12). And yet, compared to most renditions of the story, these are still quite restrained.”

Several studies for completed works are included in the exhibition (Figures 13 and 16). According to Gyllenhaal, “Siri Hurst, Lisa Knight and I can testify to the countless studies Yardumian did for each figure and for whole compositions. It took us three days to sort through his works of art on paper. The decisions leading up to a solid composition are essential to a powerful work of art. As the form and words of the requiem mass provide a solid grounding for a composer to infill with sublime music, so the implied movement and solid relationships of the objects in a painting provide a structure for the other more ephemeral elements—color, light, and ultimately, the meaning of a work.”

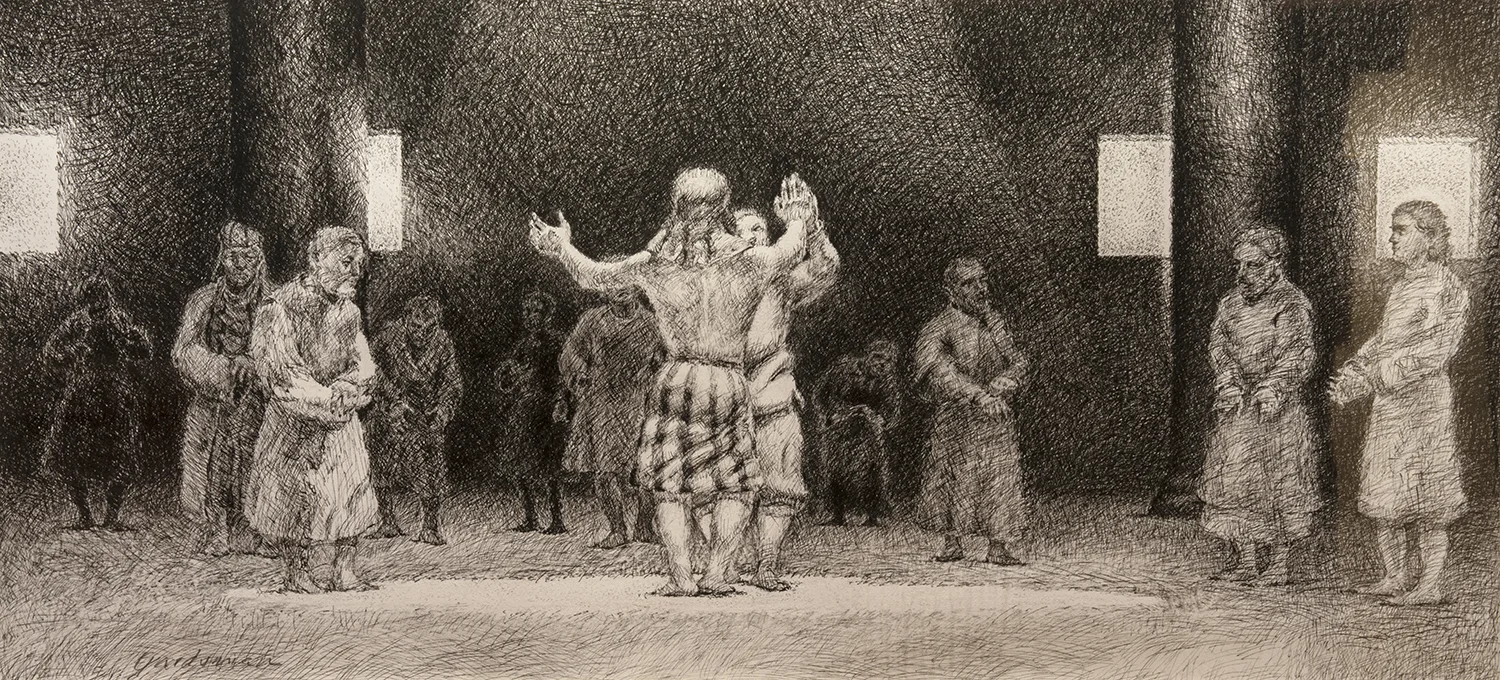

Figure 13: Joseph Revealing His True Identity to His Brothers. Study. Genesis 45:1-15. Pencil, 1985. On loan from Siri Yardumian Hurst. See Figure 14.

Figure 14: Joseph Revealing His True Identity to His Brothers. Genesis 45:1-15. Pen and ink, 1985. Collection of Glencairn Museum. See Figure 13.

Figure 15: Annunciation to Shepherds. Luke 2:8-14. Pen and ink, 1978. On loan from Ken and Glynn Schauder.

Figure 16: Annunciation to Shepherds. Study. Luke 2:8-14. Watercolor, 1977. On loan from Siri Yardumian Hurst. See Figure 17.

Figure 17: Annunciation to Shepherds. Luke 2:8-14. Tempera and oil, 1977. Collection of Glencairn Museum. See Figure 16.

Rev. Tom Rose, who was a student and friend of the artist, also spoke at the opening event for A Window to the Soul. Rose noted that Yardumian “was strongly influenced by El Greco, who was known as ‘a painter of the spirit,’ and could use light to bring the viewer into the painting and upward as if toward God. El Greco said, ‘The language of art is celestial in origin…’ He also said, ‘Art is everywhere you look for it. Hail the twinkling stars, for they are God’s careless splatters.’”

“When I was his student, Nishan taught me how to see things. That is, in terms of a scene or a subject for a painting, he showed me how to really observe the play of light and shadow, the nuances of color and hue, the way an object occupies a space. When it comes down to it, the artist who is working in paint puts down the pigment with just enough information to express himself or herself as intended. And the resulting image evokes response in the minds of others. Nishan asked, ‘To what, in us, is the picture making its appeal?’ In a painting, something has been expressed; something has been communicated. Something appears to the human mind—about the human mind and really the Divine Mind. Speaking of his work called The Annunciation to Shepherds (Figure 17), Nishan said that this image ‘would represent an idea born. The angel is an idea appearing, the shepherds are the trauma of change an idea might occasion in one’s life.’”

“I was just a mere student, and yet he openly, freely and in a fun way taught me that painting, or artistic expression, is about truth, goodness and love—divinity and humanity—as if it is a window to the soul. In Nishan’s words, ‘The artist isolates and focuses on things of the spirit.’”

At the exhibition opening, Rose invited the audience to “look around at these patches of fabric—one man’s ideas of various moods or colors of the spirit, brought together here as if woven into a garment of light. Today at this opening, Nishan Yardumian is this community’s favorite son, and surely what you see around you is his special coat of many colors.”

Figure 18: Three Angels Appearing to Abraham. Genesis 18:1-15. Tempera and oil, 1977. Collection of Glencairn Museum.

Visitors are welcome to tour A Window to the Soul: Nishan Yardumian’s Biblical Art, Tuesday through Friday as part of Glencairn Museum’s regular 2:30pm “Highlights Tour” and on weekends 1-4:30pm (walk-ins welcome), as well as by appointment and when attending the Medieval Festival. The exhibition is closed May 26 for a concert, and on July 4.

(CEG)

Photography of the artwork courtesy of Edwin Herder.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.