Glencairn Museum News | Number 1, 2022

Although he was involved in designing architecture for most of his adult life, Raymond Pitcairn was not able to read architectural drawings. Instead, he was able to participate in design work by having his craftsmen create tri-dimensional models. “My lack of training in draftsmanship and the reading of architectural drawings, I endeavored early in the work to offset through dealing with the designs in the form of scale and full-sized models” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to John T. Comes. 1920).

An examination of Raymond Pitcairn’s personal correspondence and other sources, as well as the final product—Glencairn itself—reveals what his primary motivations were for undertaking this ambitious medieval-style building project, which served as a home for both his family and his art collection.

Pitcairn considered himself an architect first, and not primarily an art collector

During the 1920s, as major construction on Bryn Athyn Cathedral was slowing down, Pitcairn found himself with time to devote to a new architectural project, as well as a readily available crew of craftsmen and laborers. At this time he also began to realize that his collection of medieval stained glass and sculpture, originally assembled in order to provide inspirational models for the Cathedral’s artists and craftsmen, had outgrown his home at Cairnwood. Perhaps the convergence of these two factors—the need for a suitable place to display his art collection, and the chance to undertake a challenging new architectural project—presented Pitcairn with an opportunity that he found hard to resist. Despite his lack of formal architectural training, Raymond Pitcairn considered himself first and foremost, not a collector, but an architect:

“For several years I devoted my entire time to the practice of architecture, and I am architect instead of lawyer for at least half my time still, and that in a very real sense,—not as mere recreation” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Leon Obermayer. 1 June 1928).

Pitcairn’s new project (which in the early 1920s he was not yet calling a “home”) was a building to display his art collection. This “studio,” as he initially described it, was to be a harmonious marriage of art and architecture and a challenging test of his architectural skills. To Pitcairn the most important work was not collecting art, but “the production of something new.” As he wrote to his brother Theodore in 1922, “the collector’s work is interesting but it is far easier than productive work”:

“One of the most striking differences between art of the past and that of today is the fact that the ancient art objects were not isolated things which were more or less forced into their surroundings, they were part and parcel of the temple, the acropolis, the house or tomb for which they were made. Our private collections as well as our museums are full of things which do not really fit their surroundings and with the introduction of oil painting on canvass, art became more and more divorced from its proper relation to the living conditions of the people. Of course beautiful things can be done where an artist understands what he is about. [George Grey] Barnard’s cloister stands head and shoulders above the private and museum collections because his objects were made part of the building which he built them into. I should like, one day, to incorporate my little collection into a studio which would be a Romanesque or early Gothic room or small building, but after all the more important work is the production of something new. The collector’s work is interesting but it is far easier than productive work” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Theodore Pitcairn. 12 January 1922).

Figure 1: This large model of Bryn Athyn Cathedral’s tower, chancel, and sanctuary was painted to resemble stone and placed on rails so it could be wheeled outside and observed in natural light. From left to right are Raymond Pitcairn, John Walker (an architect who worked for Pitcairn), and Leonard Gyllenhaal (the treasurer for the General Church of the New Jerusalem).

Although self-taught, Raymond Pitcairn’s architectural instincts were impressive. According to Dr. Andrew J. Tallon, a well-regarded scholar of French Gothic art and architecture, Pitcairn deserves to be recognized as one of two “architects of record” of Bryn Athyn Cathedral:

“The Cathedral of Bryn Athyn should be credited to not one but two architects—or rather, to use the medieval term, master builders: Ralph Adams Cram, and Raymond Pitcairn himself. As Pitcairn wrote to Goodyear in 1919, ‘while I have no desire to call myself by an architectural title, if there is an architect of record at Bryn Athyn, I am that man. . . . My work has not only governed the development and determination of the main proportions which the church has finally assumed, but it enters into the decision of final form of nearly every detail’” (See “The Refinement of Bryn Athyn Cathedral,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 7, 2014).

Many years after Glencairn was completed, Pitcairn’s sons, when asked what their father’s occupation was, preferred to give this answer: “He is a lawyer by profession, an architect by choice, and a business man by force of circumstances” (Jennie Gaskill, Biography of Raymond Pitcairn, Bryn Athyn, 1977, p. 155).

Pitcairn needed a suitable place to display his large and varied medieval collection

The difficulties Pitcairn encountered while attempting to display his medieval collection at Cairnwood, the 1895 Beaux-Arts mansion in Bryn Athyn built by his parents, played a key role in his decision to build Glencairn. A 1923 family photograph taken in Cairnwood’s main hall reveals the awkwardness of the situation (Figure 2); Pitcairn covered up the ornate French mantle of the hall’s fireplace with a curtain in order to provide a backdrop for a large statue of St. Paul. Another photograph shows that, at the other end of the hall, a 12th-century statue-column depicting a queen was tied to the stair column with a piece of wire. (See Ed Gyllenhaal and Brian D. Henderson, “The Role of the Pitcairn Collections in the Decision to Build Glencairn,” Glencairn Museum News, 27.2, 2005, pp. 1–3.)

Figure 2: Raymond Pitcairn began collecting medieval stained glass and sculpture during the construction of Bryn Athyn Cathedral in order to provide inspirational models for the artists and craftsmen. However, he encountered problems with displaying his art collection in his home at Cairnwood. In this 1923 photograph, the family poses with an arrangement of medieval sculptures in the main hall of the 1895 Beaux-Arts mansion.

But as difficult as it was to display his sculptures in Cairnwood, Pitcairn’s beloved collection of medieval stained-glass panels presented an even greater problem:

“It is quite a problem to find a place to put this glass up even temporarily to obtain a good view of it” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Richard Melchers. 11 December 1922).

For these reasons, the bulk of Pitcairn’s collections were either sent out on loan to nearby museums—such as the Academy of the New Church’s small museum in Bryn Athyn on the top floor of the campus library—or kept in storage on his estate at Cairnwood. In addition, in the early 1930s he loaned dozens of sculptures, tapestries, and pieces of furniture to the new medieval galleries at the Pennsylvania Museum of Art (now known as the Philadelphia Museum of Art). The loans to the PMA were made in several different groups from 1930 until 1935, with 49 sculptures being delivered between February, 1930 and January, 1931. (See Jack Hinton, “Reflected Glories: Raymond Pitcairn’s Loans to the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 8, 2017.) Over time Pitcairn also collected works of art from ancient Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, Classical Greece and Rome, and a variety of other cultures.

A permanent solution to Pitcairn’s problem of where to display his collection came in the spring of 1921 when he met the artist, collector, and art dealer George Grey Barnard. Barnard had recently finished building The Cloisters, a medieval-style building in Manhattan’s Washington Heights that housed his medieval art collection. His innovative ideas about how to incorporate medieval art into an architectural setting made a considerable impression on Pitcairn. By the spring of 1922, Pitcairn began referring to his own proposed building as a “cloister studio.” He also identified a possible location:

“Then when it comes to my cloister studio I hope to have some of the very best work we can do as it will be seen in conjunction with the fine examples of old glass which I have. I obtained a very wonderful Gothic statue about the time you left and I have some exciting ideas for the cloister studio, which I shall probably build on the flat piece of ground toward [Cairnwood’s] rear entrance, near the group of pine trees and evergreens” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Lawrence Saint. 6 June 1922).

The influence of George Grey Barnard and his Cloisters museum

George Grey Barnard opened his Cloisters museum to the public in 1914. The similarities between Barnard’s Cloisters and Pitcairn’s Glencairn are readily apparent to anyone who visits them today, and the influence of the former upon the latter is undeniable. In both buildings, the medieval objects have been incorporated into the fabric of the architecture in a way that allows viewers to imagine that they have been transported back in time to the Middle Ages (Figure 3). This kind of immersive experience is difficult to achieve within the neoclassical architectural settings of most museums, which usually exhibit medieval objects against painted walls and on freestanding pedestals.

According to Dr. Julia Perratore, Assistant Curator at the Met Cloisters,

“The museum was known as Barnard’s Cloisters because of the four medieval cloisters he had transported from France and reassembled on the site. These cloisters, together with many other architectural fragments, were integrated into the fabric of the museum’s church-like building, creating a setting that spoke to the religious character of much of medieval art. To further suggest the hallowed spaces of medieval worship, the museum’s guides dressed in monks’ habits, and candles and incense burned in the galleries (a fire hazard that surely would make any curator today cringe)” (“The Cloisters Connection,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 3, 2015).

As a 1927 guide book published by the museum puts it, at the Cloisters “mediaeval art is not so much on exhibition as at home”:

“For those to whom the ideal museum is a collection of labels illustrated by specimens, The Cloisters will be a disappointment. Here is no lifeless aggregation of ‘typical examples,’ so classified, so ticketed that the gentle voice of beauty is lost in the drone of erudition. On the contrary, The Cloisters is a shrine, where mediaeval art is not so much on exhibition as at home” (Joseph Breck, The Cloisters: A Brief Guide, 1927, p. 4).

Dr. Jennifer Borland, an art historian who specializes in medieval art and architecture, has done extensive research on Glencairn’s Great Hall, including a careful examination of relevant material in Glencairn Museum’s archives. Her hope was to better understand how Glencairn “reinvents the past and creates a new home for the objects through new juxtapositions.” According to Borland,

“Indeed, in the Great Hall at Glencairn, some of the works are medieval; some have been doubted or proved otherwise; and some elements were never intended to be medieval but are intentionally fabricated. But when you are in the space, experiencing all of these pieces together, it can be hard to parse out their differences. The space reframes each work, leading us to see such spaces as actively creating a new life for old objects amidst the new” (Jennifer Borland, “A Medievalist in the Archives: Exploring the Twentieth-Century Medievalism at Glencairn,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 1, 2019).

Figure 3: This YouTube video reveals how a drawing for the west wall of Glencairn’s Great Hall integrates works of medieval sculpture into the design. According to Dr. Jennifer Borland, Glencairn “reinvents the past and creates a new home for the objects through new juxtapositions.”

Interestingly, Pitcairn’s letters reveal that his new building project was not undertaken simply to display the objects in his collection that were in storage and on loan. While planning Glencairn he continued to expand his collection of medieval stained glass, sculpture, frescoes, paintings, and tapestries specifically for the purpose of installing these new acquisitions in his “cloister studio.” His letters to art dealers during this period show that he was still very much “on the hunt”:

“I notice that all of the objects mentioned in your letter are capitals and that only a few of them have columns and bases. I should also like fine bas reliefs, carved columns, fine statuary, also other architectural pieces. A set of fine large capitals that could be used in a series in a building in some such manner as Mr. Barnard has done, would be very useful” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Henry Daguerre. 27 February 1922).

“I was very glad to have your letter and the information which it contained about the glass. I do not know how I shall use it but I have had in mind for a long time the building of a cloister studio which would contain my art treasures, and if this dream is realized, your tracery panels will probably find their place in the studio” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Dr. T. M. Legge. 12 October 1922).

“In connection with the little castle which I contemplate building for my collection I should much like to have these bells and it occurs to me that you might be in a position to obtain them from him [i.e. William Randolph Hearst]” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Dikran Kelekian. 1 December 1926).

Clearly, Pitcairn’s desire to create an immersive space for his art collection “in some such manner as Mr. Barnard has done” was a key element in his creative vision, and was one of his primary motivations for building Glencairn.

Pitcairn wanted a “music hall” for musical performances and community social events

The desire to provide a dedicated space for friends and members of the Bryn Athyn community to enjoy musical performances must be included in any list of Pitcairn’s motivations for building Glencairn. It is not known exactly when Pitcairn began thinking of his “cloister studio” as a structure that would include, not just spaces for his art collection, but also a “music hall.” This may have been around 1926, the same time that he began referring to the building as a “castle”—clearly a much larger structure than a studio.

According to Jennie Gaskill, who wrote a short biography of Pitcairn, he

“wanted to continue having the musicals for which ‘Cairnwood’ had become noted. But ‘Cairnwood’ could no longer accommodate the numbers of people who always attended these musicals. So he visualized a place large enough to entertain his neighbors and friends which meant practically the whole community of Bryn Athyn. Such had been the custom from the time ‘Cairnwood’ was built [in 1895]. But then there were fewer people to accommodate. Now, in 1926, the music room soon became crowded, chairs were set up in the hall, and some late-comers had to sit on the steps which led to the second floor” (Jennie Gaskill, Biography of Raymond Pitcairn, Bryn Athyn, 1977, p. 103).

It was also in 1926 that Raymond Pitcairn wrote to Adolfo Betti, first violinist of The Flonzaley Quartet, which was about to perform at Cairnwood:

“I am sure you will have an enthusiastic little audience, and only hope you will find the occasion sufficiently enjoyable to make an annual return to Bryn Athyn. One of these days we will have our real music hall which will be much better adapted for the purpose” (quoted in E. Bruce Glenn, Glencairn: The Story of a Home, 1990, p. 148).

The next year he wrote to Betti again, this time informing him that “I’ve been working on a model for the castle with its music room” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Adolfo Betti. 30 October 1927).

It was important to Pitcairn, who was a skillful amateur musician as well as a patron of the musical arts, that his music hall have the best possible acoustical properties. In 1927 he wrote to the R. Guastavino Company, a manufacturer of ceramic acoustic tiles in New York City:

“It occurs to me that you might be willing to drop me a few lines indicating whom you regard as the authorities most competent to give advice in the designing of a large music room for a private residence in which it is contemplated to use a vaulted type construction” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to R. Guastavino Company. 28 October 1927.)

One can gain an understanding of the level of planning that went into the acoustical qualities of the Great Hall by reading the letters that Pitcairn wrote to the R. Guastavino Company between 1936 and 1937. The ceiling of the room required approximately 11,000 acoustic tiles, which were made in nine different shades of blue. Initially, Pitcairn ordered 3,000 tiles in nine shades in order to see how they would look in place (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to R. Guastavino Company. 3 December 1936). Once he saw the tiles in place, he removed two of the shades of blue, and then another shade later on, leaving a total of six different shades (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to R. Guastavino Company. 17 May 1937). In addition to the acoustic tiles, Pitcairn directed the Bryn Athyn glassworks to make yellow and blue mosaic star tiles, which made up nine percent of the total number of tiles on the Great Hall ceiling (Figure 4).

Figure 4: In order to provide a place for musical performances, the ceiling of Glencairn’s Great Hall was covered with acoustic tiles in various shades of blue. In addition to the acoustic tiles, Raymond Pitcairn directed the Bryn Athyn glassworks to make decorative yellow and blue mosaic star tiles.

At one point Pitcairn was also thinking about including an organ in the Great Hall. He wrote to Ernest Skinner, founder of the famous Skinner Organ Company, that “in planning our new residence I wish to look ahead to the time when we may incorporate an organ in our great hall” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Skinner Organ Company. 11 January 1930).

Figure 5: Since 1937 Glencairn’s Great Hall has provided the Bryn Athyn community with a monumental space for concerts, dances, and many other events. For many years Raymond Pitcairn himself taught music appreciation classes to students from Bryn Athyn College using the Great Hall’s state-of-the-art sound system (visible at the lower left of photo).

Once Glencairn was complete, the Pitcairn family was very generous with their Great Hall. The tradition of holding concerts at Glencairn dates back to 1937, when Raymond and Mildred invited the Bryn Athyn community to a Christmas concert and sing-along in the Great Hall. (This concert took place even before the decoration of the room, and construction on the building, were complete.) The space was later also used for an annual spring dance (Figure 6), school and church meetings, and many other activities. Today Glencairn Museum continues this tradition by using the Great Hall for the annual Glencairn Christmas Sing and many other cultural and educational events. The space was, and still is, sometimes used by classes at the Academy of the New Church Secondary Schools and Bryn Athyn College. In fact, for a number of years Raymond Pitcairn himself taught music appreciation classes to students from the College using the Great Hall’s state-of-the-art sound system. It seems clear that Pitcairn intended this room to support educational activities: between the Great and Upper Halls a monumental, three-story high glass mosaic depicting the official seal of the Academy of the New Church provides a colorful focal point for the room (Figure 5).

Figure 6: Throughout its life as a home, Glencairn hosted formal dances in the Great Hall for students and friends of the Academy of the New Church. In this photograph of the school’s annual spring dance, Raymond Pitcairn can be seen waving to the photographer (photograph undated).

Pitcairn wanted a new home for his family, decorated with symbolic art intended to raise the human mind to higher things

It is not yet known exactly when Raymond Pitcairn’s concept for his new building graduated from his first idea for the structure—a “cloister studio”—to a commodious home for his family. However, it is clear that Pitcairn’s dedication to his family, and his commitment to his religious ideals, lay at the heart of Glencairn’s decorative program. Raymond and Mildred were both devoted members of the New Church (Swedenborgian Christian), and Bryn Athyn was founded in the late 19th century as a New Church community. Jennie Gaskill, Pitcairn’s biographer and a close friend of the Pitcairns, has suggested that, as time went on, “Raymond’s plans were enlarged” in order to accommodate his desire to visually express his religious faith in the setting of a New Church home for his family:

“So the building began, and as it progressed, Raymond’s plans were enlarged in order that he might indulge his artistic ability in decorating with the beautiful symbolisms upon which his home life was based—a New Church home in every sense” (Jennie Gaskill, Biography of Raymond Pitcairn, Bryn Athyn, 1977, p. 102).

Pitcairn believed that the purpose of art was to raise people’s minds up to higher, more spiritual things. In a paper he delivered in 1920, and later published in New Church Life, he wrote, “The forms of art are ultimates, and they are powerful, although the origin of their power is from a higher or more interior source” (“Christian Art and Architecture for the New Church,” New Church Life, 1920). Not surprisingly, it was important to Pitcairn that the artwork he commissioned for Glencairn, his family’s new home, represent spiritual principles that he hoped would be central to the life of his family.

Figure 7: This scale model of Glencairn was photographed in the dining room at Cairnwood in the 1930s before Glencairn was completed. It included small figures of Santa Claus and his reindeer. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn’s son Lachlan remembered, “Every Christmas they had a model of Glencairn in the middle of the table at Cairnwood, and my mother would look at it and she’d say, ‘Raymond, do you think we’ll ever move in?’ because it took 13 years to build Glencairn.”

Figure 8: This plaster model of Glencairn, which for many years was put on display in Cairnwood at Christmastime (see Figure 7), is now in the collection of Glencairn Museum. In addition to figures of Santa and his reindeer, the model was originally decorated with colorful electric lights.

Exactly how were Pitcairn’s religious beliefs, and especially his love for his family, realized in the decoration of Glencairn in stone, wood, stained glass, and metal? Many of the works of art made for Glencairn recall the biblical command, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18; Matthew 22:39). Pitcairn filled Glencairn with visual symbols of four of the “neighbors” that he and Mildred hoped their family would serve during their lifetimes: Family, School, Country, and Church.

We have already mentioned one monumental example of this religious symbolism: the three-story high glass mosaic of the Academy of the New Church seal. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn were both alumni of the Academy. Their commitment to the idea of New Church education had its origin in the Academy’s goal of preparing students, not just for future employment, but for a life of spiritual purpose and service to others. The religious principles symbolized by the different visual elements of the Academy seal served as reminders of the principles to which Raymond and Mildred aspired. For example, the scene of Michael and the dragon, which illustrates a passage in the biblical Book of Revelation (12:7), represents the New Church fighting for truth and against falsity. (See “The Academy Seal in Glencairn Museum,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 8, 2018.)

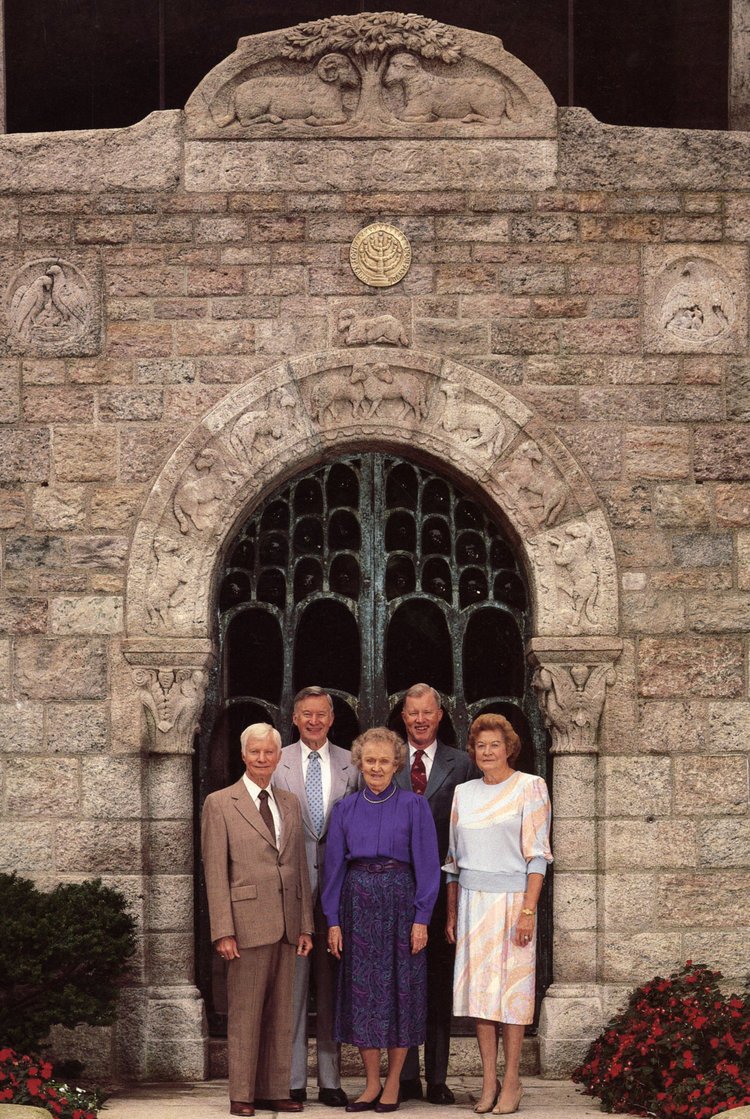

Figure 9: On the arch surrounding Glencairn’s front entrance, the nine children of Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn are represented as lambs. This photograph of five of the Pitcairn children was taken in 1989. From left to right: Michael, Lachlan, Karen, Garthowen, and Bethel.

Other examples of religious symbolism at Glencairn, created by Bryn Athyn craftsmen in a variety of media, are evident throughout the building—from the first floor to the top of the tower. The ceiling of the Great Hall is decorated with glass mosaic designs inspired by the Book of Kells, a 9th-century Celtic manuscript containing the four New Testament Gospels. A monumental fireplace in the Upper Hall features a granite relief depicting the days of creation as described in the first chapters of the Book of Genesis. The decoration of Glencairn’s Chapel includes imagery from the story of the Garden of Eden and the Book of Revelation. Repeated throughout the entire building is the motif of the grouping of ram, ewe, and lambs, which symbolizes the importance of family (sometimes nine lambs are shown, representing the Pitcairns’ nine children). Raymond Pitcairn was heavily involved in the selection of this imagery. In fact, it is known that he sometimes directed his artists to read passages from the Bible or the theological works of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) as part of the design process.

Inscriptions from both the Bible and Swedenborg are found in various places on the walls and ceilings of Glencairn. For example, a large teakwood beam above the fireplace in the Great Hall is carved with these words from Psalm 127:

“Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it.”

As E. Bruce Glenn, the Pitcairns’ nephew, has pointed out in his book Glencairn: The Story of a Home, “in the New Church it is taught that the house referred to is that of a man’s mind, his spiritual home to eternity.” However, in the context of the decoration of Glencairn, this biblical passage also expresses the wish that Glencairn would be “a home that would be a living center of family life, a home that would declare the presence of the Lord among them, so that its building might not be in vain” (p. 18, 1990).

(CEG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.